Ten years ago Bruce Springsteen cast a spiritual vision for America. It still rings true.

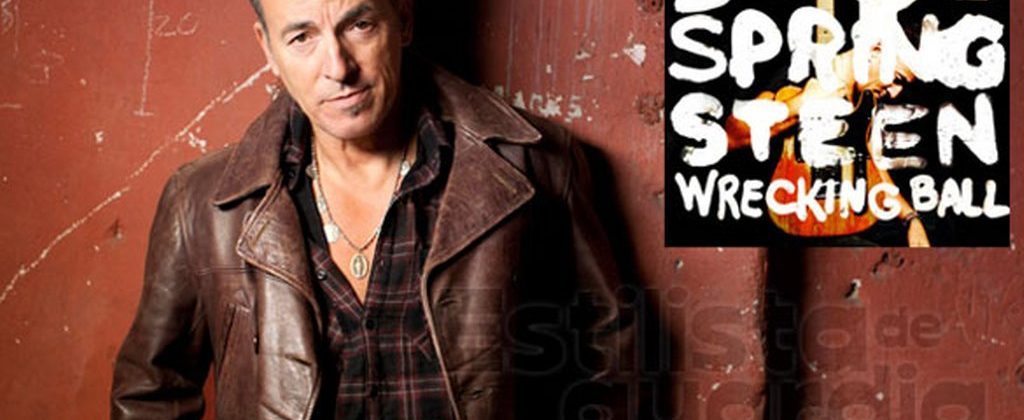

In March 2012, at age 62, Bruce Springsteen released Wrecking Ball. The songs explore themes of work, community, and the tragic yet hopeful dimensions of American life. It was during the promotion of this album that Springsteen started talking about his life’s work in terms of “judging the distance between American reality and the American dream.”

Wrecking Ball was also a deeply Christian album, filled with angry jeremiads, calls to love our neighbors, and appeals to social justice. Ron Aiello, the producer of the album, was known at the time for his work with evangelical bands Jars of Clay and Sixpence None the Richer. A decade later, Springsteen’s spiritual vision for America still rings true.

The first single off Wrecking Ball is “We Take Care of Our Own,” a rousing cry for us to fulfill the American Dream through acts of compassion and mercy to the men and women in our circle of influence. It defines the good life—the pursuit of happiness—in terms of self-sacrifice and civic virtue. In another song on the album, “Jack of All Trades,” Springsteen exhorts us to “care for each other like Jesus said that we might.” Indeed, throughout Wrecking Ball the republican tradition merges with the Sermon on the Mount to advance Springsteen’s understanding of the common good.

Wrecking Ball is also an album filled with righteous anger. In “Rocky Ground”—a song that could fit comfortably on a Black gospel album—Springsteen invokes Jesus driving the money changers out of the temple. “Death to My Hometown” is a rollicking Irish lament on the way corporate greed devastates local communities. The “robber barons” of Wall Street have “destroyed our families’ factories and they took our homes; they left our bodies on the plains; the vultures picked our bones.” And then, in “Shackled and Drawn,” we are introduced to the people who live on Banker’s Hill:

Gambling man rolls the dice, working man pays the bills

It’s still fat and easy up on Banker’s Hill

Up on Banker’s Hill the party’s going strong

Down here below we’re shackled and drawn

Springsteen’s economic populism celebrates the dignity of hard work. In “Shackled and Drawn” he equates “freedom” with a “dirty shirt” and “a shovel in the dirt.” He even suggests that labor is one way of resisting the temptations of the devil. In “We Take Care of Our Own,” work sets one’s “hands and soul free.” In “Jack of All Trades” work is something that “God provides.” It is not too far of a stretch to say that Springsteen, the product of a Catholic education, agrees with Pope John Paul II in his encyclical Laborem Exercens (On Human Work). Here the late pontiff connects labor to participation in God’s ongoing work of creation, the life of Jesus (a carpenter), and ultimately the crucifixion.

But what happens when there is no work available? What happens when the ground that we walk is so “rocky” that work is impossible to find? Whether it was the post-2008 recession or the economic devastation levied by a deadline pandemic, Springsteen does not want us to despair. Though we are drowning in “Noah’s flood,” and our prayers seem to be going unanswered, and “hard times come and hard times go,” the Boss exhorts Americans to “hold tight to your anger and don’t fall to your fears.” He asks us in “We Are Alive” (which draws on the mariachi band sound of Johnny Cash’s “Ring of Fire”) to remember the laborers, civil rights workers, and immigrants who have struggled to overcome injustice on the road to American happiness. Springsteen tells us in “Land of Hopes and Dreams” that “faith will be rewarded.” And though such faith might be “shaken” by troubled times, the “morning sun is breaking” and a “new day is coming.”

We can also trust in God’s goodness to us. Consider the words of the rap embedded in the lyrics of “Rocky Ground.”

You use your muscle and your mind and you pray your best

That your best is good enough, the Lord will do the rest

You raise your children and you teach them to walk straight and sure

You pray that hard times, hard times, come no more.

In 2012, this was one of the most explicitly Christian lyrics in the entire Springsteen songbook. He seemed to be searching for answers to questions of life that took him beyond being “sprung from cages on Highway 9” or jumping in a car with Wendy and cruising down Thunder Road. Looking back, we can see that the spiritual longings of this decade-old album foreshadowed a deeper and more sustained expression of faith in Springsteen’s 2016 memoir, his 2017 Broadway show, and his 2020 album Letter to You.

And Springsteen is not done yet. At age 72, he is planning to hit the road again with the E Street Band. Everybody’s got a hungry heart.

John Fea is executive editor of Current. This piece draws heavily from his 2012 review of Wrecking Ball published March 6, 2012 at Patheos.