The noted moral philosopher talked with Vinson Cunningham of The New Yorker. It’s a wide-ranging conversation that covers seminary students, Harvard, public philosophy, his forthcoming Gifford Lectures, Barack Obama, Democratic Socialists of America, free speech, American imperialism, Ukraine, and grief.

Here is Cunningham’s introduction to the interview:

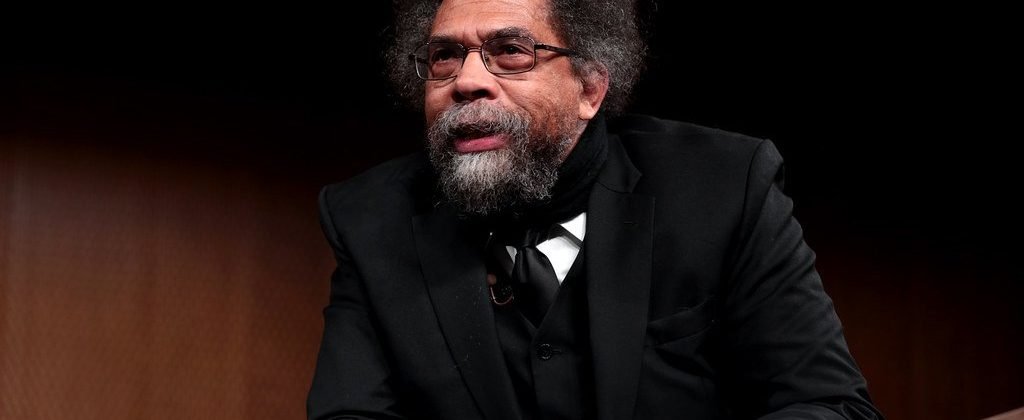

A few days after I first spoke with Cornel West, one of the preeminent public philosophers in America for three decades now, he gave a short, impromptu interview to the gossip-and-celebrity-news outlet TMZ. West was in Los Angeles, at the Sunset Plaza mall, and a TMZ reporter, recognizing him, asked for his thoughts on a comment made by Kanye West, who had recently insisted that Black History Month should be forever changed to “Black Future Month.” Kanye’s notion was that we’ve talked enough about slavery and the sundry other horrors of the past. “Ohhh, Kanye’s wrong,” West—Cornel, that is—told TMZ. “Every performance is the authorizing of a future, in the midst of the present, trying to recover the best of the past,” he said, rattling off the tripartite thought quickly and with high animation, as if he’d practiced it many times before, waiting for just this moment. “You get that in Kanye’s music, but you don’t get it in his rhetoric. There’s a sense in which his artistry is much more profound than his rhetoric.” The second time he said “rhetoric,” West forced his voice into a half-melodic and fully ironic sigh that he sometimes uses to punctuate a funny phrase. In answer to Kanye, and to others who might harbor the fantasy of a purely futuristic Blackness, West said that “as long as white supremacy’s around, you’re going to have the need to stress Black love, Black dignity, Black history—those things that are being excluded and rendered silent!”

The quick tabloid-media encounter served as a neat encapsulation of what makes West’s career and comportment unique. He is a product, and a longtime inhabitant, of the academy, having taught in tenured positions at Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Union Seminary. But he has made it a point of pride to apply his analysis to popular culture and, on occasion, to do so in popular forums. After writing academic manifestos such as “Prophesy Deliverance!: An Afro-American Revolutionary Christianity” (1982), he achieved a new degree of fame with “Race Matters,” from 1993, a collection of self-consciously populist essays addressing such hot-button topics as the Rodney King riots, affirmative action, and Black-Jewish relations. More recently, he joined the online adult-education behemoth MasterClass to teach a course on philosophy. In both 2016 and 2020, he served as a tireless surrogate for Bernie Sanders’s Presidential campaign, delivering stem-winders across the country.

When we spoke, he was in California, preparing to return to New York to resume teaching at Union Seminary, the place where he started his teaching career, in 1977. Last year, West got into a dispute with Harvard, where he had been a tenured professor more than a decade earlier, about receiving tenure again; he ultimately resigned, and used the occasion to comment on the “decline and decay” and “spiritual bankruptcy” in élite academia. The pointed note, addressed to his Harvard dean, opened in a cordial way: “I hope and pray you and your family are well! This summer is a scorcher!” It was characteristic of West, who often begins conversations that way, allowing them to radiate outward from the personal and the near at hand. He started our chat by asking after my family, and then about a book I’m writing, about R. & B. music—which I’d mentioned, over e-mail, in a brazen bit of brownnosing, since West, in his rollicking lectures, uses music (John Coltrane, Ella Fitzgerald, Curtis Mayfield, and on and on) as a symbol and a model for his ruminations on religion, politics, and race. The rest of our conversation seemed to proceed under the awning of that warm familiarity, as we discussed the crisis in secular confidence, the meaning of public philosophy, the seeming convergence of radical and reactionary attitudes toward American interventionism, and many other things. We spoke twice: once, at length, before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and once, briefly, afterward. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Read the interview here.