The first of a two-part series on how the Christian Right fell in love with and then started to sour on George W. Bush

On December 13, 1999, six weeks before the 2000 Iowa caucuses, the candidates for the Republican Party nomination for President of the United States met in the Des Moines Civic Center for their first debate. The men on stage, seated from left to right, were Steve Forbes, the publishers of Forbes Magazine; Alan Keyes, the former ambassador to the United Nations’ Economic and Social Council in the Reagan administration; George W. Bush, the governor of Texas; Orrin Hatch, a U.S. Senator from Utah; John McCain, a U.S. Senator from Arizona; and Gary Bauer, the president of the evangelical Family Research Council. Tom Brokaw of NBC News and John Bachman of WHO-TV in Des Moines moderated the event.

The most talked-about moment of the debate came near the end, when Bachman asked each candidate to identify the political philosopher whom they most admired. Forbes mentioned John Locke; Keyes, the founding fathers. And then Bush, with little hesitation or set-up, said “Christ—because he changed my heart.” Bachmann followed up by asking Bush how Christ changed his heart. “Well, if they don’t know, it’s gonna be hard to explain,” the Texas governor said, “when you turn your heart and your life over to Christ, when you accept Christ as Savior, it changes your heart and changes your life.”

The camera flashed to Keyes, who seemed stunned by the answer. As one of the most experienced Christian culture warriors on the stage, he was probably wondering why he did not give it. Hatch was next. He said that he agreed with everything Bush said, and then added Abraham Lincoln and that great political philosopher Ronald Reagan to his list. McCain, ever the reformer, referenced Teddy Roosevelt. Bauer, the director of James Dobson’s evangelical family organization, also mentioned Jesus. His answer was predictable, and though it did get a round of applause from the audience, by this point it was too late. Bush had already seized the evangelical high ground.

Richard Land, the president of the public policy arm of the Southern Baptist Convention, was watching the debate on television. In an interview that appeared the next day in The Washington Post, he said that when his wife and daughter heard Bush’s answer they “stopped what they were doing,” looked at Land, and said “Wow!” Land added: “Most evangelicals who heard that question probably thought ‘That’s exactly the way I would have answered that.’” Newsweek writer Howard Fineman put it best: “People from New York or San Francisco saw that statement by George W. Bush and probably were aghast, or laughed, or said, ‘here’s a guy who’s been presented with an essay question on his philosophy paper and can only come with Jesus. How pathetic.’ But among conservatives in the Bible belt, in the heartland, places where Jesus seems as present as the highway or the strip mall, that was a sensation.”

Bush’s claim that Jesus was his favorite philosopher was an authentic response from a guy who had had a legitimate conversion experience. As several commentators noted during the campaign, he was not trying to court the Christian Right vote in the way that his father or Reagan had done. Rather, George W. Bush was the Christian Right. His eventual election filled the Christian Right with hope and a sense of possibility. American culture was changing rapidly and, from the perspective of most conservative evangelicals, it was changing in all the wrong ways. But the Christian Right could take comfort that Bush was in its corner.

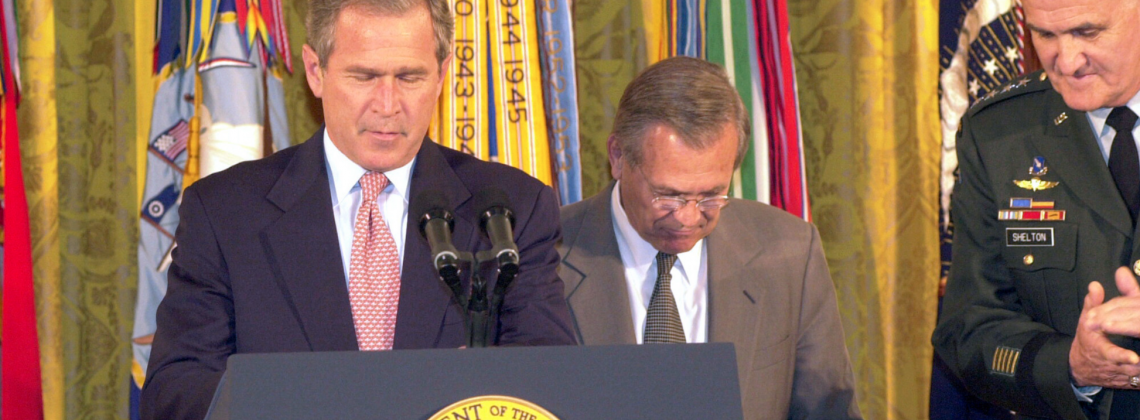

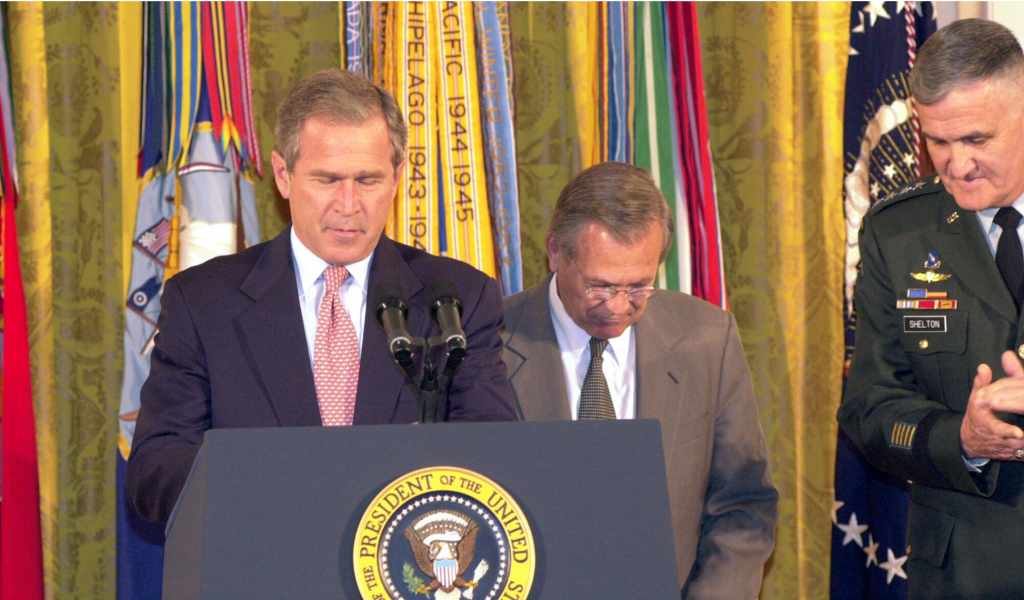

For much of his first term in office Bush was everything the Christian Right hoped he would be. He instilled patriotism in the country following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. He presided over a war in Afghanistan and Iraq that was not only “just” but that also served to protect the interests of Israel. He opposed embryonic stem cell research.

But nothing excited the Christian Right more than when Bush publicly endorsed a federal amendment to the United States Constitution that defined marriage as the union of one man and women. On November 18, 2003, in the landmark Goodridge v. Department of Public Health, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court required the commonwealth to recognize same-sex marriage. In the weeks that followed, cities across the country, from San Francisco to Asbury Park, New Jersey started issuing marriage licenses to same sex couples in the hopes of generating a similar case to Goodridge in their own states.

In a February 24, 2004 speech, Bush said that “ages of experience have taught humanity that the commitment of a husband and a wife to love and to serve one another promotes the welfare of children and the stability of society. Marriage cannot be severed from its cultural, religious, and natural roots without weakening the good influence of society.” Bush called upon Congress to “promptly pass and to send to the states for ratification an amendment . . . protecting marriage as a union between one man and one woman.” This, he believed, was the only way to prevent “activist courts” from redefining this institution.

Over the course of the next several months Republicans in Congress worked hard to garner enough votes in support of a federal marriage amendment. But in July the Senate voted 50-48 to end debate on the issue. The Christian Right was not happy. The Family Research Council released a press release titled “50 Senators Invite Unelected Judges to Usher in Same-Sex Marriage.” A spokesperson for the lobbying group described the rejection of the amendment in the Senate as “round one.” It was now time to “begin training” for round two. Charles Colson of the evangelical Prison Fellowship Ministries said that the Senate vote was merely the start of what he predicted to be a “ten-year fight.” (He was only off by a couple years). James Dobson of Focus on the Family compared the vote to the American Civil War: “This is the opening salvo in a long battle to preserve the definition of marriage as the union of one man and one woman . . . a battle we are determined to win. Mississippi’s Republican Senator Trent Lott told his constituency that “The Federal Marriage Amendment will be back.”

In the weeks that followed, many conservative evangelical political activists turned their attention to Bush’s re-election. The GOP convention was only a month away and there were platforms to write and voting guides to publish. The fight over marriage would have no chance without a Bush win over Democratic challenger John Kerry in November.

But when the Christian Right learned about the Bush campaign’s plans for the convention, they began to wonder, for the first time, if the guy who believed Jesus was his favorite philosopher was the right guy to advance their vision for America into the twenty-first century. (To be continued.)

John Fea is Executive Editor for Current.