It runs both ways

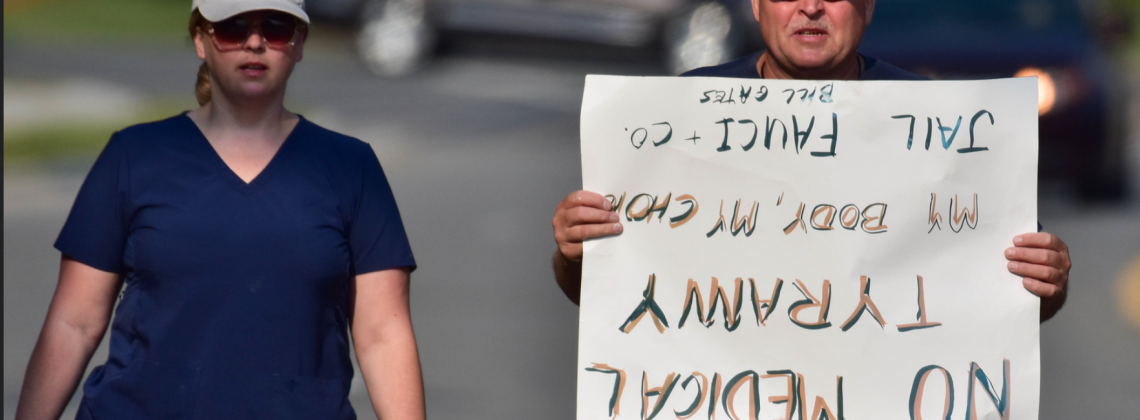

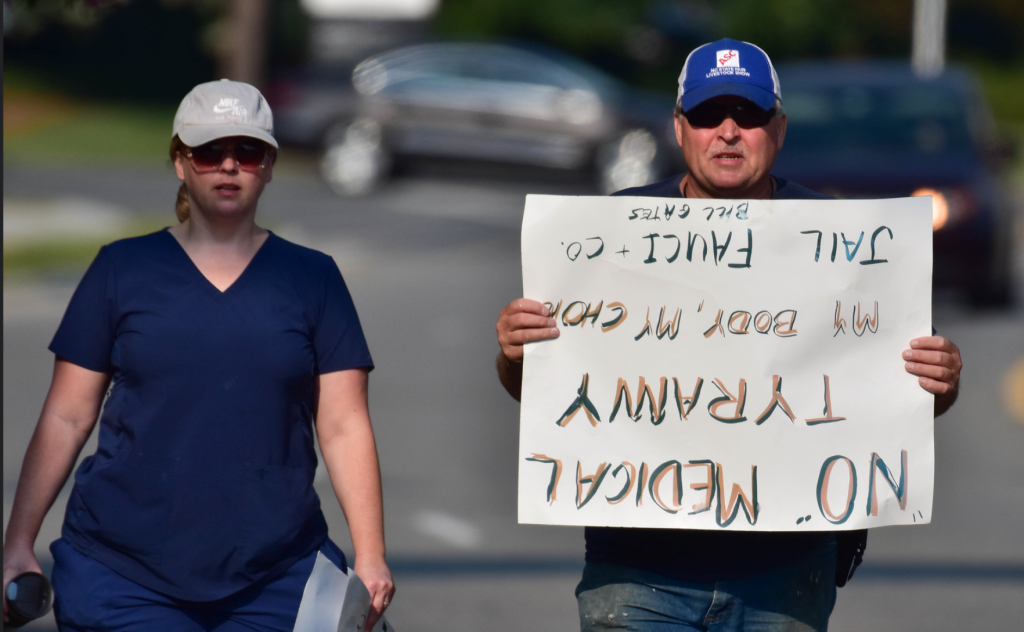

At the two-year mark of the pandemic, revelations abound. Among them: We Americans believe we have the right to reliable, on-demand professional services. It is an assumption that has worked its way into our social contract, as seen in the headlines. We protest at school board meetings, threaten government officials, and demand health care—and of the most sophisticated variety. The professions exist for us; their service is our due. This is our belief.

It is a lie.

Professions are, in fact, bodies that exist to offer service. But they have no obligation to offer it. Ours is, famously, a free country, after all.

And it is a free country in need of a renewed experience of freedom. To get there, we might begin by probing the frayed relationship between the professions and the public.

The professions—engineering, education, law, and more—provide specialized and demanding service that flows from long traditions of thought and care. It is the ideal of service—seen emblematically in the Hippocratic Oath—that guides them. From the posture and practice of service the professions gain their distinctive forms of intelligence and wisdom.

Professions are self-governing bodies. They are not the property of those being served. For their own success the professions require a proper autonomy; for the sake of those they serve the professions must operate within the bounds of their own authority. Things go reliably wrong when this authority is breached—when, for instance, non-engineers build bridges, non-historians declaim on the past, non-legal scholars pronounce on the law, and non-statesmen ascend to high office.

For a variety of reasons we have lost sight of the worth of this expertise, and thus a necessary sense of our own dependence on it. We have taken the service that professionals offer—something beyond our own capacity to do as well, or at all—and turned that care into a right, part of the “quality of life” about which we, in our least impressive moments, boast.

That which the professions offer to a society is a gift. Why have we forgotten this basic and salient reality?

We have forgotten it in part because the professions themselves have forgotten it—as seen in their failure to cultivate an ethos of service. Gifts proffered from on high to the citizen down below do little to foster gratitude in the recipient. (Nor does bestowing better gifts to those who pay more, for that matter.) Noblesse oblige wins only the hearts of the servile. A functioning sense of dignity—one of democracy’s great gifts—demands more of us.

And when professions raid their repositories of public goods for personal gain or pleasure, any nobility a profession might deserve dies a necessary death. If the great professional traditions exist to shine light, offer healing, and build a people, woe to the professional body whose guardianship of that trust perverts its truest aims. Who would contend—in an age of unending sexual abuse scandals and rank corporate profiteering—that these failures have not corroded the public trust? As the ecological costs of high-tech modernity become more evident, the role of scientific, financial, and legal professionals in its shortsighted reign will only add to our resentment and alienation. The nobility of “professional service” is suffering death by oxymoron.

In a more philosophic sense, the professions’ varying intellectual traditions can themselves turn from being treasuries of truth to seedbeds of falsity. False doctrine in any field disorients and destroys. Bad practices turn out bad results, however earnest the practitioner. If my own professional field, history, shuts out the foundational philosophic debate its own growth requires; if a system of organization keeps medical specialists from holistic understanding; if economic pressures lead engineers to narrow apprehensions of their achievements, then the intellectual traditions upon which the professions are built fall into disrepair.

When this loss of integrity occurs, it is often the professionals who are the last to know. Pretension clouds the eyes, and we go on constructing our fiefdoms (teachers unions, bar associations, government agencies, and more) on weak foundations. The damage is predictable—as predictable as the injustice of who will bear its cost. Remember the (ahem) Emergency Economic Stabilizing Act of 2008—the great Wall Street bailout?

Skeptical regard of the professions, then, and protest against professional overreach are not just warranted. They are necessary, from both within and without.

But for protest and confrontation to have constructive effects they must emerge from a posture of humility. It is dependency, after all, that grounds our common condition. As isolated citizens, we cannot teach our children all they need to live well. Nor can we keep planes flying, roads paved, or even our bodies alive. Our dependency requires of us a humble stance.

Humility manifests itself in gratitude, and gratitude strengthens union. Out of gratitude we take measures to ensure that teachers work in safety, are paid well, and are pedagogically free. Out of gratitude we volunteer at the polling place. Out of gratitude we help keep our health workers well so they can keep us well.

For their part, those who are aiding us, profession by profession, must do so in a spirit of elemental respect—a respect that honors the hearts and minds of those they serve: our fears, our thoughts, our hopes, our limits.

Such humility is hard enough in any age. But in the midst of our intensifying civic crisis, how much more! The resolute secularity of the professions has ensured that culture-war conflict has emerged in all professional spheres—not simply politics and education. If the professions have engineered our much-vaunted progress, that progress has come at the cost of secularization, and with it the attendant conflict.

Add to that the capitalist economy’s part in elevating (and making lucrative) many of the professions, but at the cost of class stratification, increasing inequality, and mass resentment. Our many fissures—social, intellectual, political, ecological—run along the lines these forces have set firmly in place. What can we do?

We can turn from the big picture to the small one—the one small enough to make visible the power of gratitude and respect. The surgeon who extended my father’s life with a valve transplant is surely worthy of respect—a respect that will incline me to trust his profession when it offers a vaccine. But in the same spirit, the teacher who takes my child into her care must see a vulnerable, infinitely valuable human person with a lifetime of consequential choosing ahead.

The sheer reality of any child is, in fact, enough to re-center all of our institutions and practices, from medicine to education to the economy itself. But first we need to see her, with eyes lit by the deepest wisdom we know.

Perhaps then we’ll sense—company by company, office by office, school by school—that we’re bound together not by professions of expertise but by professions of love. This is the pathway to freedom—and to any progress worthy of the name.

Eric Miller is Professor of History and the Humanities at Geneva College, where he directs the honors program. His books include Hope in a Scattering Time: A Life of Christopher Lasch, and Brazilian Evangelicalism in the Twenty-First Century: An Inside and Outside Look(co-edited with Ronald J. Morgan). He is the Editor of Current.