Once upon a time, a big shark got everyone talking—and watching

I was nine years old in 1975, “The Summer of the Shark.” Jaws was released then, and no one who didn’t live through the following few years can fully appreciate the change that movie brought. Star Wars happened in 1977 but Jaws had already set the precedent and was still resounding; I suppose the only comparable impact was that of the Harry Potter books, much later.

Before Jaws there was no concept of the summer blockbuster. Movies were released at different times, often near the holidays. Jaws came out on June 20th, and as the hot months went on it continued to devour the box office as people kept seeing it, telling friends about it, and seeing it again. It outsold this famous movie, then that one, then another one. The ominous music became a universal language. Shark books were checked out of libraries. For the next five or six years I wanted to be a marine biologist or a Coast Guard officer so that I could be on or in the sea. Everyone was talking about Jaws.

There were two ways to see movies in those days: in the theater or on network TV, whenever the networks decided to bring them out, usually a year or so after the theater release. There was no way to own a movie in a home library—no VHS cassettes, no DVDs, no streaming. Video stores hadn’t yet appeared. Particular movies were wondrous events that bloomed like rare flowers, and you had to be there when they did.

If you were a kid in love with a movie, you might get your parents to take you to a drive-in theater. With your cassette recorder you could try to capture the sound from the speaker hanging on your car window. You would glare at your parents if they coughed or mumbled something about popcorn. Then in the weeks afterward you could listen to that scratchy recording and let the glorious movie replay in your mind. You could buy the LP soundtrack and listen to it over and over, the music transporting you into that magical world. In either case, you needed your memory of the visuals. You could read the novel if it had come first, as in the case of Jaws, or the novelization if someone had churned out a paperback to mirror the film. That was the era of the advertising slogan, “Read the book! See the movie!”

Jaws knocked our culture off its feet. Its director, Steven Spielberg, had wrangled a PG rating because he wanted the most people to be able to see it. Even so, the movie shocked Americans. Here was intensity and gore like we’d never seen: a severed head . . . a woman and a child snapped up . . . a man savaged in a shark’s jaws . . . the iconic severed leg sinking toward the ocean floor. Such things simply had not been shown on a screen before. Reports flooded in of people becoming ill in theaters, having heart attacks. It only fueled the fire. People wanted to see Jaws.

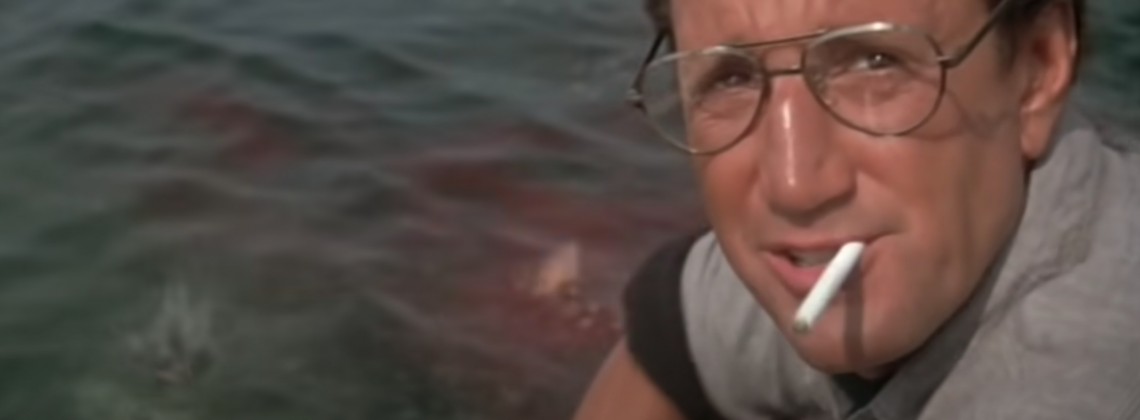

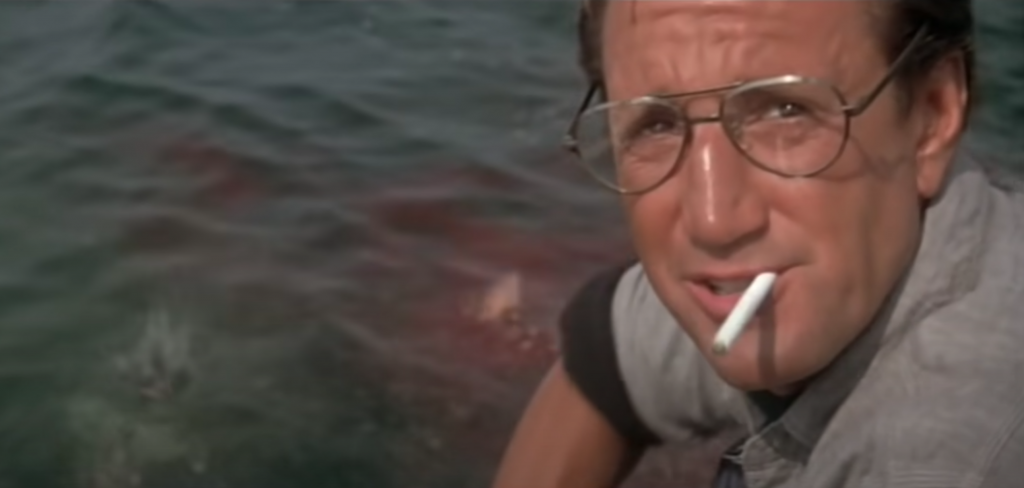

And the swearing. This was an era when, if a movie character said “shit” audiences would giggle in nervous glee. We were years away from the f-bomb. In one of the most famous scenes well into the film, when the shark is first shown, Spielberg exercised his genius in his purposeful audience manipulation. He knew he could convert a laugh response into a scream of terror. Chief Brody, aboard the Orca with his back to the deep blue sea, is shoveling chum—a mixture of fish guts, blood, and watery brine used to attract sharks. Brody finds the task of chumming unpleasant. As he protests, looking toward the camera, the 25-foot shark rears from the sea behind him, so close that scraps of chum land on its head. Brody is saying, “Slow ahead! I can go slow ahead. Why don’t you come down here and chuck some of this shit?” He says the delightful, naughty word, and just as the audience laughs, the shark appears. The SHARK! The laugh becomes a scream. Spielberg, a relative unknown, takes his place beside Hitchcock.

Moviegoing was more communal in those days. The viewers weren’t in their own bubbles. They were people seeing a movie together. No one had cell phones to silence. They laughed, they cried, they shrieked . . . and when something on-screen took them into a place of deep shock, they had to talk about it. Whole scenes of Jaws were inaudible because the audience needed to process aloud what they’d just experienced. They had to grab the arms of the people they’d come with and talk about how they felt. It wasn’t just an exclaimed word or a sentence. They had to climb out of the world they’d been immersed in and get back into the world they knew, touch the people they loved, share words, and assure themselves that the illusion was just an illusion. It’s much rarer to experience this in theaters now, but it happened then. (I’m told that superhero movies today are still somewhat communal.)

The problem facing my Cousin Phil and me was that we were young boys, nine and ten. We wanted more than anything to see Jaws. We had both already read Peter Benchley’s novel. But Jaws had such a reputation that our parents were skeptical. (Little did they know that the graphic extramarital affair on which the book spends so much verbiage is not even in the film.) At around the same time, Phil and I each got the permission we needed, but we were each hesitant to tell the other for fear that the other had not fared as well. I saw Jaws twice in the same weekend, with different people. In all, I believe I saw it ten times before it left theaters. I can’t even count how many times I’ve seen it since. It was the first movie my wife and I watched on our honeymoon. It had to be so: It was Jaws.

For me, Jaws remains the gold standard of movie storytelling. It’s the screen story against which all others are measured. It’s perfect: nothing wasted, every possibility teased out, all building toward the inevitable climax. It is the textbook for aspiring filmmakers.

But beyond craft, it is a story, and it hit me at the best possible time of life. I was in that last precious stretch of being a kid, seeing wonder in the world. Jaws delivered: peril, gore, suspense, courage, integrity, bad-assery, self-sacrifice, adventure. There is no moment like the one John Williams on the soundtrack labels “One-Barrel Chase,” when Quint seems to have the upper hand, when the Orca is racing in pursuit of the shark, and even Brody, despite his terror of the sea, is smiling. Jaws raised our expectations of the movies. It was exhilaration, a new world.

Twice in the film, the question is asked, “Have you had one do this before?”

Twice in the film, the emphatic answer is, “No.”

For over twenty years, Frederic S. Durbin has been professionally writing fiction for adults and children. His most recent novel, A Green and Ancient Light, was named a Reading List Honor Book by the American Library Association.

Excellent review of an all-time favorite. I had just graduated from college in 1974 (I’m SO old) and had read the book. My first date with my now husband was to see the movie. He’s quite a tease, so I warned him not to touch me during the scary parts, since I knew where they all were… But when the head dropped out of the bottom of the sinking boat (NOT in the book!) I shrieked and grabbed him!! We still laugh about that.

As a librarian I generally believe that the books are better than the movies based, often very loosely based, on them. But Jaws the movie was a great improvement on the book. Even when I read it I found the extramarital affair to be unnecessary to the story, as tho his publisher forced Benchley to add it.

Thank you for writing this!