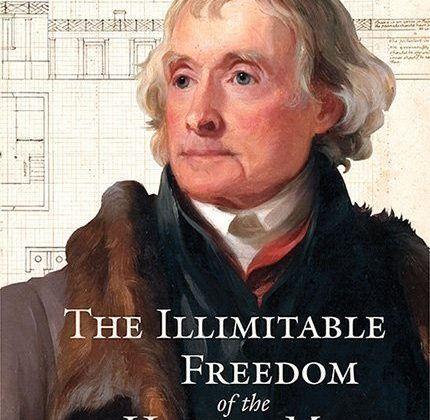

Andrew O’Shaughnessy is Vice President of The Thomas Jefferson Foundation and Saunders Director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies. This interview is based on his new book, The Illimitable Freedom of the Human Mind: Thomas Jefferson’s Idea of a University (University of Virginia Press, 2021).

JF: What led you to write The Illimitable Freedom of the Human Mind?

AO: As the Saunders Director of the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies at Monticello since 2003, I became aware that Jefferson’s obsession with the creation of the University of Virginia was largely treated in secondary literature as an epilogue to his career, despite the fact that he regarded it as one of his three greatest achievements to be inscribed on this tombstone with the Declaration of Independence and the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. My desire to write on the subject was additionally stimulated by my colleagues at Monticello, who edit the Papers of Thomas Jefferson (Retirement Series), which include the documents for the founding of the University of Virginia.

JF: In 2 sentences, what is the argument of The Illimitable Freedom of the Human Mind?

AO: All too often treated as an epilogue in the life of Thomas Jefferson, this book makes the case that that the creation of the university is deserving of his own estimate as one of the three greatest achievements and that it had an important but unappreciated influence upon higher education in America. The book argues that he was motivated by the desire to create a secular and republican university to undermine what he regarded as a dangerous stranglehold on education by Presbyterians and Federalists in both the North and the South.

JF: Why do we need to read The Illimitable Freedom of the Human Mind?

AO: The subject of the founding of the university remains relevant because Jefferson was concerned with what remains a perennial issue: the civic importance of education in the success of the republican/democratic experiment. He had a creative vision that still has the potential to inspire and to stimulate discussion. In contrast to the bland mission statements of the majority of modern universities, his own description of the role of universities was poetic, emotionally engaging, and highly resonant even today, such as his famous invocation of what he regarded as the most valuable of all liberties, “the illimitable freedom of the human mind.” The university was just the apex of a much broader vision of public education and his desire for what he called “a general diffusion of knowledge.” In 1779, he advocated and wrote a bill for public education when no country had a comprehensive state secondary education system. As the founding statesman most frequently quoted for his anti-government sentiments, he nonetheless made a case for the enlargement of government – admittedly at the state and local level – for the purposes of education.

Like the Declaration of Independence, the university project was tainted by the presence of slavery. The loftier aspirations of Jefferson’s vision for the university were not fully realized. Nevertheless, this remarkable personal achievement and the richness of his vision deserve wide recognition. In the context of the United States, this book argues that his ideas were distinctive and unique, but that the revolutionary elements have either become too widespread to be novel or have disappeared. He anticipated many of the features of the modern university. As one of the driving passions of his life, this account reveals underappreciated elements of Jefferson’s abilities, and his skills through which he aimed to encourage progress and extend happiness among a greater number of people. It is historically unparalleled among heads of state or former heads of state to have devoted such interest in envisioning and creating every aspect of a university from surveying the land, designing the buildings, writing the legislative bills, overseeing the construction, listing the books for the library, suggesting the curriculum, developing criteria for selecting the faculty, to inviting every student to dine at Monticello. It was all the more remarkable given that he began in earnest at the age of 73 and continued until the last months of his life at the age of 83.

JF: Why and when did you become an American historian?

AO: My family background played an important role in influencing my future as an American historian. From the time that my father began teaching at Columbia University in 1968, I and my brother made biannual visits to the United States. It made me curious about the links between the histories of Britain and America. The schools in Britain did not teach much about the American Revolution.

In my early teens, I had wanted to make a film documentary about the history of my village and began visiting the local archives to find information. The project soon became unwieldy. The local archivist suggested that I study a family by the name of Payne who have lived in the village in the eighteenth century while owning slave plantations in the British Caribbean islands of St. Kitts and Nevis. The topic had a special attraction since the family had commuted two centuries earlier across the Atlantic. I wrote my first article for a local magazine about one member of the family who had been a radical politician in the early nineteenth century and had lived in the same village called Blunham in Bedfordshire. As an undergraduate student at Oxford, I wrote a prize winning essay on the rise and fall of the plantations owned by the Paynes. This inspired my doctoral thesis which set out to investigate the extent of support for the American Revolution in the British Caribbean and eventually resulted in my first book An Empire Divided: The American Revolution and the British Caribbean (2000). In the process of writing it, my interests shifted to the American Revolution.

JF: What is your next project?

AO: Writing this book introduced me to a travel journal of Edward Stanley to America in 1824-25. He later became three-times Prime Minster and the longest serving opposition leader in Britain, as the 14th Earl of Derby. A hundred copies of the journal were privately published in the 1920s but it is otherwise unknown in the United States. It is possibly one of the best such travel accounts of the nineteenth century because of his focus upon education, slavery, race, and Native Americans. It is important because the experience was to shape his political career, especially his role in abolishing slavery in the British Empire.

JF: Thanks, Andrew!