As the Birmingham campaign shows, listening and confrontation go hand-in-hand

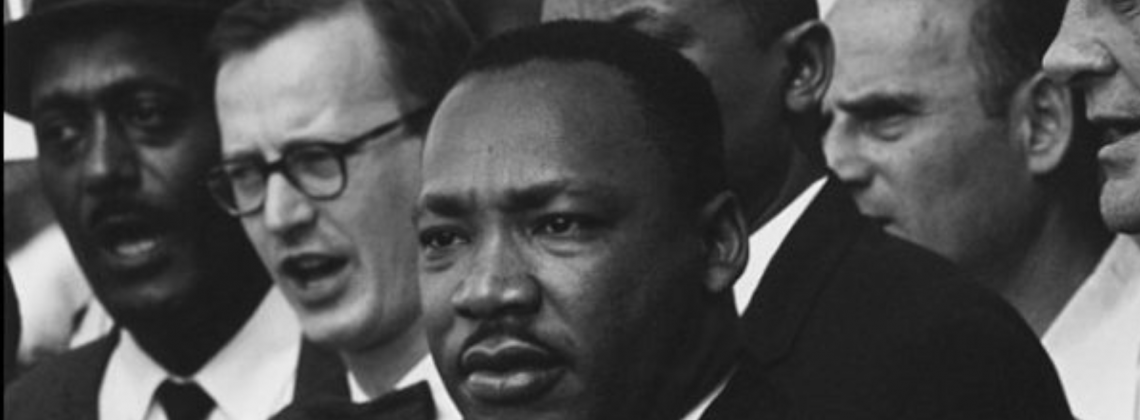

In April and May of 1963, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference organized what became known as the Birmingham campaign, a coordinated effort to protest the practice of segregation in Birmingham, Alabama.

Martin Luther King, Jr. had called Birmingham the nation’s most segregated city. He hoped that mass demonstrations could pressure the city’s bosses into making long-awaited changes. Thousands participated in non-violent protests and many were arrested on trumped up charges, filling the local jails to capacity.

We’ve all seen those black-and-white newsreels of demonstrators being confronted with police dogs and mowed down with fire hoses. The Birmingham campaign featured all of this and more.

With uncommon courage and perseverance, Dr. King’s non-violent protesters accomplished what they set out to do. That is, they raised the pressure to such a level that change became a considered option. But it was also dangerous. Like a pressure cooker with no relief valve, an eventual explosion was all but certain if a peaceful and acceptable settlement couldn’t be brokered. The success of the campaign was in jeopardy and tensions were stratospheric.

So, the two sides sat down together. On one side of the table were campaign leaders advocating for civil rights; on the other side were intransient segregationists determined to maintain the racial status quo. Against all odds, a deal was struck that gave King and the other campaign organizers much of what they wanted. Jailed protesters were released on their own recognizance. In short order, lunch counters, restrooms, and drinking fountains were desegregated. Hiring practices were altered. That fall, Birmingham’s schools were integrated.

It’s important to note that despite these encouraging breakthroughs, all was not well. Resistance to change soon became even more escalated and violent. In September of that year, four African American girls were killed when Klansmen bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church, an event that contributed to the city’s scornful nickname, Bombingham. The Birmingham campaign had its successes. But progress advanced in fits and starts for a very long time.

Still, a question remains: What happened in that meeting room that caused hidebound segregationists to accede to the campaign’s demands? Did King and his negotiators overwhelm them with the strength of their logic? Did they threaten them in some way? Did they shame them into submission? Did they utilize some sort of Jedi-like power to transform their intransigence into acquiescence? What exactly did the campaign negotiators do?

The short answer to that question: They listened.

To be certain, there was more to it than simply that, but the power of listening evidently played a significant role. Reflecting on the Birmingham campaign in his book Why We Can’t Wait, King recalls what one staunch defender of segregation said of Justice Department official, Burke Marshall, who helped negotiate for the campaign: “’There is a man who listens. I had to listen back and, I guess, I grew up a little.’”

But how could listening have diffused such an explosive situation? I’d like to make three observations about the power of listening and then bring us back to this question.

First, listening builds or destroys relationships. “It is impossible,” said Swiss physician and author Paul Tournier, “to over-emphasize the immense need people have to be really listened to, to be taken seriously, to be understood.” The human capacity to form close relationships begins as early as infancy through the mother’s empathic attunement to her newborn. Perhaps few things in life are as emotionally satisfying as being heard and understood by someone we care about. Listening builds connective relational tissue.

But the converse is also true. Perhaps nothing hurts more deeply than to be summed up inaccurately and to be given no way to correct the misperception. The stance, “My mind is made up, my conclusions about you are chiseled in concrete, and nothing you say will change my opinion” is emotionally devastating. Connective relational tissue is shredded when people refuse to listen.

Second, listening deescalates tensions. Those who work in trauma and recovery understand this axiom: When threat reactions elevate, reasoning responses decline. Like a seesaw, when the part of your brain designed to protect you from danger goes up, the problem-solving part of your brain goes down. That’s why the advice is often given: Don’t make big decisions in the midst of a crisis.

That said, those who work in emotionally charged situations are trained to deactivate their threat reactions so they can maintain calm when crises occur. That’s very counterintuitive and doesn’t come naturally. When Captain Sullenberger, for example, landed his plane on the Hudson River in 2009, he was asked how he had pulled off something so heroic. He responded that he didn’t see it as heroic because pilots train for such scenarios. When the crisis occurred, he tipped his seesaw accordingly. He had trained himself to keep his threat reactions deescalated so that his ability to think clearly could remain heightened.

Third, listening precedes resolving. Those who practice Alternative Dispute Resolution help opposing parties walk through several steps to achieve mediated solutions. One of those steps involves listening—where both sides understand the other side’s position and why taking that position is important to them. Mediators understand that when people feel heard and understood the tensions deescalate. So important is this facet that mediators won’t let the process advance until such validation has been achieved. What’s true in mediation is true in all close relationships. No relational problems are ever solved when people feel unheard or misunderstood.

Now back to our question: How did the campaign negotiators pull it off? The above-stated propositions about listening help explain why the negotiators’ listening would have had such a diffusing effect. I can only assume that these things happened in that room:

- While he completely disagreed with the segregationists, Marshall listened to their views and sought to understand their concerns (“There is a man who listens.”)

- Being heard resulted in reciprocal listening (“I had to listen back.”)

- Listening paved the way for a reasonable solution (“I guess I grew up a little.”)

The point of this piece is not to suggest that listening is all that’s needed to transport us into the sunny uplands of relational and social harmony. Nor is it reasonable to suggest that listening will always lead to successful mediations, since some people enter the process pre-determined to never budge an inch. But it would be accurate to suggest that listening is a necessary prerequisite for reaching solutions to personal or societal problems. When threats go up, reasoning goes down, and listening along with it. And when people stop listening to each other, tensions will only stay elevated.

Listening first and concluding later rather than the other way around is always needed—but perhaps never more so than in times characterized by the old phrase, “You’re saying it so loud that I can’t hear what you’re saying.”

May it be said of all of us, There is a person who listens.

Alan Godwin has practiced as a psychologist in private practice in Nashville, Tennessee for over 30 years. He is the author of How to Solve Your People Problems: Dealing With Your Difficult Relationships (Harvest House Publishers). He also serves on the adjunct faculty of Trevecca University where he teaches doctoral students and has traveled nationally presenting continuing education courses for mental health professionals.

Alan Godwin has practiced as a psychologist in private practice in Nashville, Tennessee for over 30 years. He is the author of How to Solve Your People Problems: Dealing With Your Difficult Relationships (Harvest House Publishers). He also serves on the adjunct faculty of Trevecca University where he teaches doctoral students and has traveled nationally presenting continuing education courses for mental health professionals.