Is society a conspiracy against freedom? Or is it freedom’s hope?

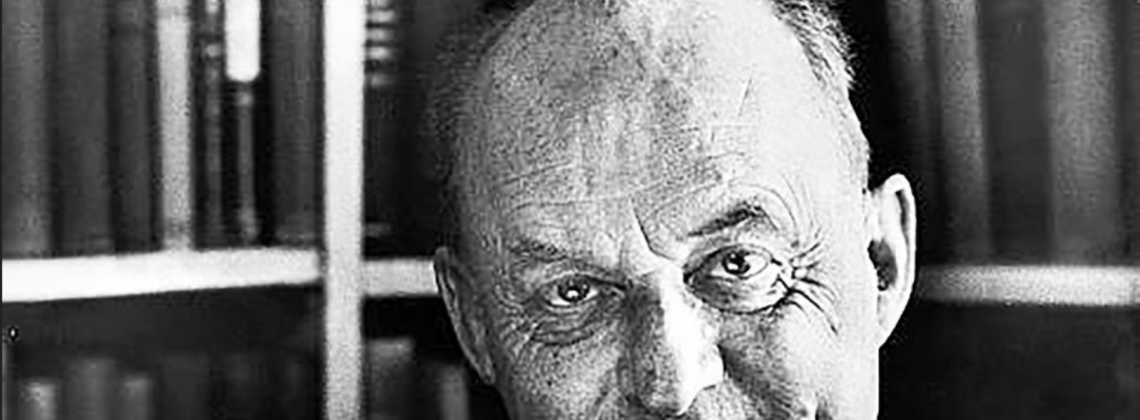

This past summer I was privileged to participate in a Current “Deep Water” video conference with Jeremy Sabella, author of An American Conscience: The Reinhold Niebuhr Story. Niebuhr’s standing as a kind of court theologian to the Cold War policy elite makes him a central figure in mid-twentieth century intellectual life, yet his reputation suffered in the wake of post-Vietnam disillusion with America’s self-image as the defender of global freedom. Sabella rightly notes that whatever his responsibility for American’s Cold War hubris, Niebuhr was also a major influence on the most undeniably righteous politics of mid-century America, the Civil Rights movement. In his 1932 masterpiece, Moral Man and Immoral Society, Niebuhr speculated that some adaptation of Gandhi’s tactics of non-violent resistance might just be the best path for African Americans to take in their struggle for justice. Martin Luther King read Gandhi, but he also read Niebuhr.

I first encountered this sympathetic revision of Niebuhr in the 1980s as an undergraduate student of the great U.S. intellectual historian, Christopher Lasch. Reflecting on the ongoing debates over Niebuhr, it occurs to me that none of the participants has ever questioned the basic premise of Niebuhr’s social ethics: Individual men may be moral, but society will always be immoral.

Niebuhr’s argument proceeds from the very modern notion that conflict is at the heart of human relations and that the purpose of society is to manage or contain it. True, Niebuhr sees in non-violent resistance an opportunity to transcend the endless check-and-balance of interest vs. interest, but even Gandhian non-violence takes place within a framework of conflict. Non-violence does indeed offer the possibility of productive, transformative conflict through a love of enemy; still, this noble tactic for achieving justice has provided little guidance for the proper ordering of everyday life. After the great Civil Rights victories of 1964 and 1965, King faced opposition from a younger generation of African Americans with their own vision of Black Power. Women and sexual minorities in turn took up struggles for justice in the name of newly discovered rights. King’s vision of a “Beloved Community” foundered on the very American notion that society everywhere is in conspiracy against the freedom of every one of its members.

No one can doubt that conflict is part of social life. But only modern man has made it the essence of social life. The traditional Christian view is the exact opposite, and some of the earliest settlers of the colonies that would become the United States brought this understanding with them. John Winthrop’s famous lay sermon, “A Model of Christian Charity” (1630) has survived in the canon of American literature for its image of the Massachusetts Bay Colony as a “city on a hill,” a beacon of light to the nations. Winthrop invoked this image to reflect his hope that the righteous example of Puritan New England might inspire conversion among the unrighteous Christians back in Old England, yet his vision of society extends far beyond personal piety:

GOD ALMIGHTY in his most holy and wise providence, hath so disposed of the condition of mankind, as in all times some must be rich, some poor, some high and eminent in power and dignity; others mean and in submission . . . that every man might have need of others, and from hence they might be all knit more nearly together in the Bonds of brotherly affection. From hence it appears plainly that no man is made more honorable than another, or more wealthy, etc., out of any particular and singular respect to himself, but for the glory of his Creator and the common good of the creature, man.

This ideal of an organic, hierarchical society is profoundly traditional, medieval, even Catholic. It contrasts sharply with the later social visions associated with the “city on a hill,” be they nineteenth-century utopian communities or the twentieth-century life-style enclaves chronicled by Frances Fitzgerald in her Cities on a Hill (1986). Winthrop was neither naïve nor idealistic. The reason he affirmed the goodness of society is precisely because he knew that people themselves are not good. Mutual dependence, not moral or spiritual autonomy, helps to make man moral and pious.

This vision had guided Christian society for a millennium, but it could not survive a single generation in New England. Historians continue to debate the reasons, but theology certainly played a key role. The Puritans set themselves apart from England to pursue an authentically Christian life, but soon some began to question the righteousness of Puritan society itself. Figures like Anne Hutchinson and Roger Williams began to assert, in different ways, a privileged access to truth against the authority of the community. The seeds of spiritual individualism began to sprout early on, though they would not truly blossom until the nineteenth century. By that time, political and economic changes would reinforce the primacy of the individual. As society seemed to be spinning out of control, social reformers sought to restore order by promoting individual virtue and piety, a movement perhaps best captured by the idea of “temperance”: Abstaining from alcohol will ensure social order; social order is the fruit of the discipline and self-control of each individual.

This strategy was, ironically, more symptom than cure. The idea of making society moral by making each individual within it moral reflects a loss of understanding of society as something more than an aggregate of individuals. This is precisely what alarmed the person most associated with coining the term “individualism,” Alexis de Tocqueville. The individual, according to Tocqueville, forsakes “society at large.” This individual is not, however, totally isolated from all people. That is, he is not the fully alienated or “atomized” individual of a later sociological tradition. According to Tocqueville, individualism “disposes each member of the community to sever himself from the mass of his fellow-creatures; and to draw apart with his family and his friends” [italics added]. Far too many commentators on Tocqueville neglect this aspect of his analysis; they conflate family and friends with community itself, missing Tocqueville’s concern for a sense of society beyond a private circle of family and friends. Tocqueville is himself partly responsible for this misunderstanding. Fearing social anarchy, he placed his hope for social order in the flourishing of voluntary associations, which he believed could mitigate the centrifugal force of democratic individualism.

Subsequent history has not borne out this hope. The virtue of association was more than mitigated by the principle of voluntarism. “Society at large” is not the product of human will. We receive society; we do not create it.

Commentators who share Tocqueville’s concerns have often looked to religion to fill the empty space left by the passing of “society at large.” Sadly, in America religion itself is more often than not deeply animated by the voluntarism of democratic individualism. Still, if a certain kind of theology shares some of the blame for stripping society of its goodness, another kind of theology might provide an antidote. The organic vision of society Winthrop inherited has its parallel in the understanding of the Church as the Body of Christ. Perhaps a more robust living of the Church as the Body of Christ might inspire a more robustly moral society, despite the persistence of immoral man.

Christopher Shannon is associate professor of history at Christendom College in Front Royal, Virginia. He is the author of several works on U.S. cultural history and American Catholic history, including the forthcoming American Pilgrimage: A Historical Journey Through Catholic Life in a New World, due out in the spring of 2022 from Ignatius Press.