Critical race theory is flawed. Banning it is far worse.

Alabama’s state board of education will soon debate whether to criminalize critical race theory.

“Critical Race Theory” is code for saying “White People Benefitted from Slavery More than Black People.” That’s not really what the theory is. But that is what conservatives intend it to mean when they unveil it as a bogeyman.

Whatever the problems of critical race theory (and there are some), the Republican solution is worse: They propose to ban any lesson or information that might make someone (including whites) feel bad about the past. They will save kids from critical race theory by refusing to teach the history of slavery.

So if slavery makes students feel bad, they don’t have to learn it.

And that’s really dangerous.

Critical race theory is an easy target, since it’s not actually taught in public schools. When Alabama’s state superintendent initiated a temporary ban on critical race theory in August, he acknowledged that he couldn’t find critical race theory in any Alabama public schools. (So you can see why they needed to ban it.)

Critical race theory is also roiling the Virginia governor’s race. The Republican wants to ban it; the Democrat rolls his eyes.

Eye-rolling isn’t going to solve the problem. Democrats (and Republicans, for that matter) should call these measures what they are: attempts to remove discussion of slavery from our public schools.

None of the efforts to stop “critical race theory” actually use the words “critical race theory.” They use far more insidious language. The proposal bans “concepts that impute fault, blame, a tendency to oppress others, or the need to feel guilt or anguish” to persons on the basis of their race.

Slavery in America was in fact based on race, so most of the documents and discussions of slavery must deal with how one group felt about another group. The primary sources—the voices of people from the past from which we write history—are saturated with discussions of race.

If the standard of Alabama is that no one can ever be offended or feel bad, then these codes mandate that if any student feels bad about slavery, the lesson—however true it may be—must be rejected.

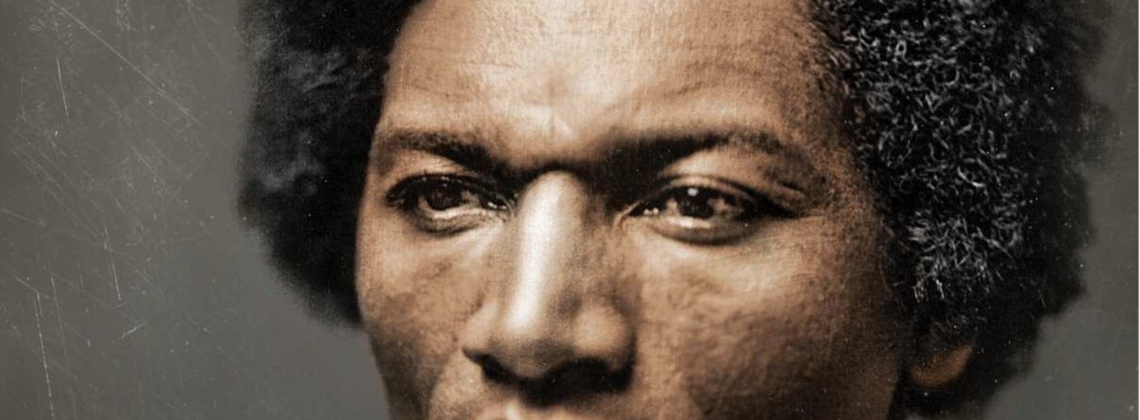

To take one example: Former slave Frederick Douglass wrote that in 1830s Maryland “anyone with a white face” could stop and question him. More, he noted that “White men have been known to encourage slaves to escape, and then, to get the reward, catch them and return them to their masters.”

Will this historical truth offend white students? If so, Douglass’s Narrative—the most important slave narrative ever written—could be banned in Alabama.

What about when Douglass condemns “the white man’s power to enslave the black man”? Douglass wrote at length that the law gave white people rights it did not give to non-whites. “If I had been killed in the presence of a thousand colored people,” wrote Douglass, “their testimony combined would have been insufficient to have arrested one of the [white] murderers.”

What is a teacher to do? Say that Douglass was wrong?

The Alabama Board of Education can either say Douglass was wrong (a historical absurdity), or (more likely), simply bar Douglass from the classroom.

And Douglass is pretty mild compared to others. Thousands of public records contain phrases that reveal race-based prejudice. Consider this one from a private, white citizen in 1789 Virginia: “I have appointed Patrollers to Keep our Negroes in order & search all Disorderly houses after night.” If a teacher showed this document to students, someone could feel that all whites are being blamed. So: no discussion of slave patrols.

So what will teachers teach? Probably this: “Slavery was a moral outrage. It was part of the culture and caused many challenges. It was many years before Americans could end slavery.” The end.

This is the real Republican goal: to keep mentions of slavery brief and vague. To focus on happy things so that the American drama becomes a story of opportunities realized and challenges overcome—a story which, as James Loewen writes, makes it impossible to understand our current crises.

The ban is clever, too: it only censors concepts. The letter of the law allows students to read Douglass—they just can’t say how Douglass’s account shows how slavery in nineteenth-century America gave whites benefits over blacks.

Discussions of race, power, and slavery are banned.

This slavery-lite history means the Civil War gets explained as white soldiers and hardtack rather than the dynamics of the slave system itself. Alabama’s ban supports Alabama’s state-supported Confederate Memorial Park—which explains that Alabama seceded from the union “to save its economic position.”

The point is to never bring slavery up, so that children learn not to question slavery, or its legacy, or why overwhelmingly Black high schools in Montgomery bear the names of Lee and Davis.

The problems don’t end with slavery. What about Woodrow Wilson? Wilson segregated federal agencies and famously declared that “Every hyphenated America hides a dagger that he is prepared to thrust into the heart of this country.” He invaded Mexico and Haiti, and did nothing as lynchings proliferated across the nation.

The Alabama ban prevents teachers from even discussing Wilson. They can’t teach that Wilson hated immigrants, Jews, and Blacks because that would make white Protestants feel bad. But they also can’t teach that Wilson hated all those people because it might make everyone else feel bad.

So what will they teach? “Woodrow Wilson was the 28th president of the United States. He led the nation into World War I. He was born in Staunton, Virginia.”

The Republicans, in short, want to mandate that everyone feel good about history. It doesn’t matter what kids know, just what they feel.

They have somehow combined the worst parts of political correctness and Christian nationalism at the same time.

Yes, there is an actual “theory” behind critical race theory. It dates back to the 1970s. It argues that racism and racist thinking are hardwired into American institutions. The theory is notoriously hard to understand and like several modern approaches to race, it has drawbacks. (John McWhorter discusses them here.)

But these bans are far worse than any academic theory that is (not) circulating in schools.

Republicans have picked an obscure academic theory as a means to remove all discussions of race and American slavery from public schools, to write slavery and race out of history so that it’s easier not to worry about race in the 2020s.

If slavery is our national sin—and it was a sin—then by extension the study of American history is going to involve the study of sinners. If the forced relocation of Native Americans was a crime—and it was a crime—American history is going to involve the study of criminals. The fact that among the sinners and gangsters we can find saints and heroes is the remarkable thing: the part that makes American history worth knowing and studying not in spite of its flaws but precisely because of them.

Republicans are betting that Americans would rather never discuss slavery. Democrats—and concerned Republicans—should be warning people how wrong that would be.

And historians like me need to speak up for primary sources, Frederick Douglass, and the truth.

Adam Jortner is the Goodwin-Philpott Professor of Religion in the History Department at Auburn University. He is the author of the Audible series Faith of the Founding Fathers and was part of the creative team behind Where in Time is Carmen Sandiego?

Adam Jortner is the Goodwin-Philpott Professor of History at Auburn University. He is the author of The Gods of Prophetstown and Audible original series including Faith and the Founding Fathers and American Monsters.