How easily we forget the strangeness of the body

I started a new job in August of 2020. After nearly a decade in higher education, I left the ivory tower for the corporate world, launching a career as a business analyst at a software company. My degrees in writing and theology had (obviously) prepared me well for software integration projects. Making a drastic life change in 2020 was also on brand. I weathered it with the same tranquility and general goodwill that seemed to hang in the air.

The pandemic had taken a late-spring, early-summer staycation—which, we are now gathering, may be an annual thing. But already the virus had proven itself resilient. The hopes of a quick turn back to global un-catastrophe were dead. Teachers settled into the dreary frustration of online education. Kids who had been raised on maxims of “limiting screen time” found themselves in front of tablets and desktops for long stretches each day with the expectation, perfectly reasonable, that they would proceed with their schoolwork as normal. Parents googled how to get alcohol delivered.

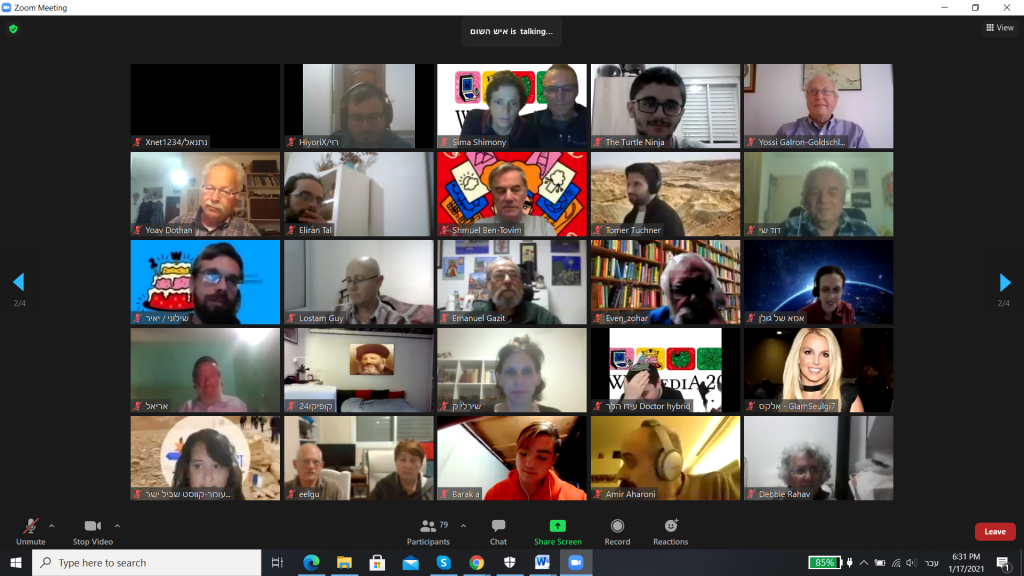

At that point, most organizations were still flailing to learn the technology that would keep them afloat. A lot of faces spent a lot of time too close to cameras. Each of us came to recognize and despise the way our own chins look. And the wish for more able use of the mute button became universal. The internet finally won the presidency—or better yet, hegemony.

My company was one of the lucky few that had already invested in a remote workforce. Pre-pandemic, about 70% of its 300 employees were 100% remote. They knew how to use the internet. They made ample use of the mute button.

Coming from higher ed, where technological ineptitude was playing its strongest hand, it was jarring to step into a world where remote work was normal. My company had transitioned, easily and without complaint, to a fully remote interview process. It had, with some pain, moved its twice-annual company-wide meeting/party to Zoom, making it more of a meeting and less of a party. It had made allowances for parents with young children and Covid-special cases. But otherwise, the work went on more or less as normal.

Learning a new job online was hard. Being introduced to coworkers via Google Hangouts or instant messages in Slack was awkward. Having meetings—I mean actual meetings; efficient, productive meetings—day in and day out over video call was a steep adjustment from the world of academia. There, the feeling that pervaded every virtual gathering was distrust and discontentment, as if video calls were placeholders of a once-and-future productivity rather than a viable means of achieving anything in the present.

The new job was lonely, though. I felt that keenly. This style of remote work was productive and efficient—my team made forty hours look like ninety—but I missed people. I missed the friendly office banter and spontaneous hallway conversations of my old job. I missed the easy social overlap of in-person work: lunch breaks to favorite restaurants, quick walks to coffee when 2pm showed up tired and dull, the occasional happy hour at the end of a day. A 9am Google Calendar event with a written agenda and a Meet link attached wasn’t quite the same. That was a time to make deadlines, not friends.

Slowly I learned the social norms of remote work: (1) Long silence after a question is not a sign of disagreement or apathy: clicking the unmute button takes more time and dexterity than opening your mouth. (2) It is perfectly normal to join a meeting and proceed with the work you were already doing until the group is called to order; small talk is not required. (3) When a meeting is over, someone needs to close it decisively, with words; fidgeting is not effective through a screen.

It surprised me, but I got used to it, the whole thing. I’m still a Luddite working at a software company—but the efficiency of it all appeals to me. Credit my latent New Yorker sensibilities.

I even made friends. It shocked me, but as the months passed, relationships formed, somehow, and deepened. I felt a growing desire to meet these people in the flesh.

After the vaccine came out, I did meet a few of them. A year into my job, I’ve had three in-person encounters with coworkers. I have met a total of seven people, seven something-like-friends. Let me tell you: It was not business as usual.

All three times, the shock of seeing people in three dimensions has been difficult to move past. They just look different than they do on the screen: their faces narrower, their shoulders thicker, their hair a different texture or shade. And their shape is off. I don’t mean “off” from some prescribed standard of beauty, but off from what I (who knew?) expected. I had no way of realizing how thoroughly my imagination had filled in the frames of the people on the screen (or totally erased them, it’s hard to say which) until I met them in the flesh and was appalled: They were taller, shorter, bigger, smaller. Of the seven, I did not meet a single one who didn’t shock me.

There was more to the discomfort than that, though. The social rules of the screen did not apply in person, and I floundered in the lack of them. It was as if I was trying to remember what it was to be a body in the presence of another body—how to make eye contact, enough of it and at the right time, how to laugh, how to show I was paying attention, how to interrupt.

But it’s not accurate to say I didn’t remember how to be with people. I had not, after all, spent the last year in a cave equipped with wi-fi but stripped of all human contact. I had been with people. I just hadn’t been with these people. It wasn’t the generic body I didn’t know how to relate to or interact with. It was Tim’s body, Caroline’s body, James’s body.

The experience has convinced me, if I ever lacked the conviction before, that human beings are not brains on sticks. To relate to other people in friendship, esteem, love, commitment—or even in disgust and dislike—is inevitably and ultimately to relate to creatures of flesh and blood, three-dimensional and strange in shape. I have formed real friendships over the screen. But such friendships, by their very nature, it seems, call for more than two dimensions. They demand depth—the thickness of bodies, the strangeness of shapes taking up the same space.

The ask feels risky, though. What if I do it wrong? Fail to achieve the right level of casual when I cross my legs? Go to put my hands together but miss my right with my left? Avoid eye contact for too long the first minute and hold it for too long the next?

Such slips will be there in these friendships, I think, until we learn how to be in the same room. But if we do learn, we might just wind up the kind of friends that show up for each other in the flesh—to funerals and weddings, to a really good meal, to a contagious fit of laughter: the well-worn material of three dimensions.

Deanna Briody is a writer and poet who works as a business analyst at a software company in Pittsburgh.

Deanna Briody is a writer and poet who works as a business analyst at a software company in Pittsburgh.