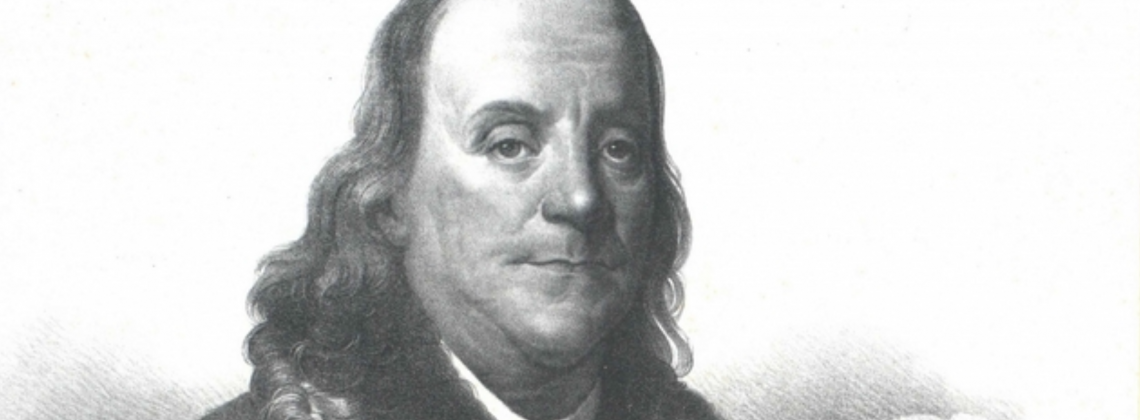

If you want to know what college students think about the values that define America, ask them to write a review of Ben Franklin’s Autobiography. Over the last twenty years I have read hundreds of these reviews, written by the undergraduates enrolled in my entry-level early American history course. The assignment is on my syllabus again this Fall.

Franklin was a great man—arguably the greatest American ever. He was an inventor, a civic humanist, a successful businessman, a founding father, and a diplomat. My students love the guy they encounter in the Autobiography. He is a model of virtue, community service, intellectual curiosity, and, perhaps most importantly, the self-improvement necessary to achieve the American Dream.

Most of them, however, did not know that he was a terrible father. For example, Franklin all but disowned his son William, the governor of the colony of New Jersey, when he chose to stay loyal to the British during the American Revolution. The governor made several efforts to reconcile with his father following the war, but Ben rejected every one of them. William’s political sin was unforgivable.

If Franklin’s treatment of his son is not enough to rile the moral sensibilities of my Christian students, his relationship with his wife, Deborah Read Franklin, certainly is. Deborah would become a trusted partner in Franklin’s print shop—a “good help-meet,” as he called her. But upon his retirement in 1748, Franklin began his pursuit of a life of “publick affairs” and, as a result, things changed quickly in their relationship.

In 1757, he was sent to London to represent the Pennsylvania Assembly and, with the exception of a two-year stint in Philadelphia between 1762 and 1764, would remain there for the rest of Deborah’s life. Her health deteriorated while Ben was gone and she suffered from depression and a stroke, the latter of which she blamed on her husband “staying so much longer” in England.

Some of my students think twice about Poor Richard when they learn that he rejected the Calvinism of his Puritan parents and affirmed that “the most acceptable Service to God was doing Good to man.” While they are generally sympathetic to Franklin’s attempt to live by certain moral virtues, they measure his religious life against their own evangelical variant and find it wanting. Many wonder what America would be like today if the revivalist George Whitefield had only tried a bit harder to convert Franklin when he had the chance.

Occasionally, students are disturbed by Franklin’s thoughts about the relationship between race and American cultural identity. Poor Richard was quite concerned, for example, about the large number of German migrants arriving in Philadelphia and its hinterlands. He asked why Pennsylvania was allowing “Palatine Boors” to “swarm into our settlements” and “establish their languages and manners to the exclusion of ours.”

Similarly, they are surprised to learn that Franklin, despite his role in the founding of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, owned slaves most of his life. It would not be too far a stretch, as historian David Waldstreicher has argued, to suggest that slavery was essential to Franklin’s meteoric social rise.

By bringing outside information about his family life, religion, and views on race into the seminar room, I am able to humanize Franklin for my students and get them to see him as a product of the eighteenth-century world in which he lived. This is one of my primary tasks as a history professor. Yet too often my students prefer to focus on the trees and miss the forest. Eager to point out Franklin’s specific triumphs and foibles, they fail to engage critically with the central message of the Autobiography and the way Franklin’s philosophy of life has shaped them.

The Autobiography, printed in twenty-two separate editions between 1794 and 1828 and still in print today, has always taught Americans something about who they are, where they have been, and where they are going. Mark Twain once said that Franklin’s moral lessons and pithy maxims “brought affliction to millions of boys . . . whose fathers had read Franklin’s pernicious biography.”

Take, for example, the way Franklin connects work, industry, and frugality to the pursuit of material gain. His Way to Wealth, a collection of wise sayings from his popular Poor Richard’s Almanac, has appeared in 145 editions and has been translated into seven languages. It is one of America’s great capitalist manifestos. And it has led many of Franklin’s harshest critics to portray him, as historian Gordon Wood once wrote, as a model of “America’s bourgeois complacency, its get-ahead materialism, its utilitarian obsession with success—the unimaginative superficiality and vulgarity of American culture that kills the soul.” If good Americans just work hard enough, all their dreams will come true. Today the ghost of Ben Franklin embodies just about every self-help author, prosperity preacher, and motivational speaker in the United States.

I often end my discussion of the Autobiography by asking students a few questions: If Benjamin Franklin and Jesus ever met, would they have things to talk about? Is there a difference between the person who orders his or her life around Franklin-esque self-improvement and the person who orders his or her life around a divine call?

My students are often shocked to learn that my wife and I did not tell our children that they could “be anything they wanted to be” as long as they put in the effort. Instead, we encouraged them to find a vocation—the kind of work, to paraphrase spiritual writer Frederick Buechner, that they “must do” and the “world most needs to have done”—and pursue it.

Progress is a good thing when it corrects blatant social injustices or improves the lives of ordinary people. Franklin’s scientific and civic experiments made life better for eighteenth-century Philadelphians. But progress can only take us so far when understood in terms of what Franklin called the “perfectibility of man.”

The human freedom and impulse to create, innovate, and pursue justice must always be balanced with the belief that we live in a broken world. As good Americans, my students gravitate toward the former but are not always willing to work at coming to grips with the latter. They prefer Franklin’s America—a place of liberty, social climbing, and happy endings. And it is even better when they can baptize those pursuits of happiness in the river of divine blessing.

I vividly remember visiting Franklin’s Philadelphia gravesite with a group of students a few years ago. As we stood in silence before the tombstone for a moment or two, the lesson was clear: The quest for human improvement in this life always has its limits. This is why we hope for the day when shalom is restored and all is made new. We long for the day when, to quote Springsteen, “we’re gonna get to that place where we really want to go, and will walk in the sun.” This is not a place that the teachings of Ben Franklin, or any other American hero, can take us.

Bring on the new semester!

John Fea is the Executive Editor at Current