Thirty-nine years ago this month my life changed as the result of a simple act that took place while seated at the kitchen table in the northern New Jersey house where I grew up. With all the faith I could muster, I repeated aloud the words in the back of a small devotional booklet called Our Daily Bread. I asked God to forgive me of my sins, I accepted by faith Christ’s redemptive work on the cross, I asked for strength to live in accordance with the teachings of an inspired and authoritative Bible, and vowed to take seriously Jesus’s call in the Great Commission (Matthew 28) to “go into all the world and make disciples.”

For the last four decades I have worked to bridge the divide between the reality of my everyday life and the high spiritual ideals to which the Spirit called me that day.

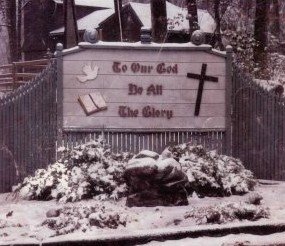

Millions and millions of people around the world have had born-again experiences similar to mine. While such conversions are deeply personal in nature, they rarely occur outside of some kind of spiritual community. My parents prayed a similar prayer of salvation months before I did, prompting them to leave the Roman Catholic Church of their childhoods (and my childhood) and join a newly-planted congregation in West Milford, New Jersey called Gilgal Bible Chapel.

The Christians at Gilgal welcomed our family with open arms, and for the next several years I threw myself into the life of this community with abandon. I was a regular at Wednesday night youth group, served as a leader in the junior high ministry on Friday afternoons, devoted my summers volunteering as a counselor in the church day camp, and spent Saturdays hammering nails as part of a Habitat-for-Humanity-like construction ministry that helped those in need.

During these years—roughly 1982-1984—I do not remember a single discussion about politics ever taking place. I also don’t remember ever hearing the word “evangelical.” We called ourselves either “Christians” or “born-again Christians.” We were not trying to “win back the culture” for Christ. Instead, we understood ourselves as a faithful remnant trying to live by the ethics of the Kingdom of God in a sea of New Jersey secularism.

Opportunities for spiritual growth and ministry abounded at Gilgal. My father became a church deacon and took a leadership role in the Saturday construction ministry. An ex-Marine and son of Italian immigrants, he raised me and my brothers with an iron fist. His spiritual conversion, participation in the life of Gilgal, and the reading of Christian writers such as James Dobson and John MacArthur softened him, making him a better father and husband. My mother taught Sunday school, participated in women’s Bible studies, and worked in the church day camp. Gilgal afforded her opportunities for ministry and service she never had in our Catholic parish.

Gilgal’s pastor–let’s call him Pastor Dan– taught a Bible study at our house on Friday nights. Each week dozens of people crammed into our kitchen to learn more about how to live a Christian life. We eventually needed to buy more folding chairs to accommodate the overflow of people who sat in our adjacent dining room and living room. Several of my mother’s six siblings and my father’s twin brother converted as part of this Bible study. These were exciting times. God was on the move.

For the middle-class families who attended Gilgal, there was much about the place that functioned like any other congregation. There was a Sunday morning and evening service, a mid-week Bible study, and a host of weekly ministries. But Gilgal also attracted a large number of single Christians. These young people came from around the world with a desire to live in spiritual community and minister to others. They were missionary kids, Wheaton College graduates, former drug dealers and alcoholics, and twenty-somethings just searching for meaning and purpose in life. They resided together in a large house on the twelve-acre campus. When I graduated from high school, I got a first-hand taste of this side of Gilgal.

Those who resided at Gilgal, along with a smattering of locals who still lived with their parents, made up a group called “Workmanship.” (The name came from Ephesians 2:10.) Workmanship met every Sunday afternoon. A typical meeting usually began with Pastor Dan—a giant of a man at about 6’5 and more than 300 pounds—confronting one of the members about what he believed to be their sinful behavior. The most popular sins on Pastor Dan’s radar screen—such as pride and individualism—were those that threatened community life at Gilgal. Those who were not willing to sacrifice their “rights” (Pastor Dan used this word in a negative sense) for the larger mission usually found themselves on the hot seat. In other words, a Workmanship meeting was nothing short of a weekly intervention. It was not until I arrived at Philadelphia College of Bible in the fall of 1984 that I realized not all born-again churches functioned this way.

Pastor Dan surrounded himself with a group of elders. With the exception of an insurance salesman named Chuck, who spent most of his time ministering to church families outside the Workmanship orbit, these elders were mostly lackeys of Pastor Dan. On Saturday nights, some of them locked themselves in Pastor Dan’s personal study to watch R-rated movies. Other elders chided families for taking too many family vacations, buying cabins in Vermont, or questioning Dan’s authority. Usually Chuck was left to clean up the mess.

I left Gilgal sometime in 1989, just before things got really ugly. My parents stayed through the revelations of Pastor Dan’s sexual harassment, adultery (a long relationship with a member of Workmanship who was married to an elder), and efforts to hold on to leadership at Gilgal in the wake of these indiscretions. Today only the summer camp remains.

I experienced a level of spiritual growth at Gilgal that I have not experienced at any other church since. I developed a passion for reading, study, teaching, and Christian thinking in this community. But Gilgal also made me deeply suspect of authoritarianism in all its forms, distrustful of other Christians, and wary of talking about my spiritual life with anyone who is not in my inner circle of family and close friends.

In light of what I experienced, one might be surprised to learn that I was never a candidate for the #ExEvangelical community now popular on Twitter. Many of my friends and acquaintances during those years either took this route or gave up Christianity entirely. But others became pastors, missionaries, seminary professors, and responsible members of more mainstream evangelical congregations.

As I look back on my time at Gilgal, I often ask myself if the good things I experienced there outweigh the bad. I have finally come to the conclusion that this is the wrong question. As writer Richard Rodriguez once said, “life is a whole.” There is a sense in which we betray ourselves when we refuse to accept that the past has shaped us—for both good and bad—and simply rest in that.

I do know this: I still believe in the authority of the Bible, the necessity of the New Birth, the redemptive work of Christ on the cross, and the need to share my faith—in word and deed—with others. For all the faults that historians and pundits point out about evangelical Christianity—and there are many—I have also seen the power of the Gospel that I first encountered at Gilgal forty years ago manifest itself over and over again in the form of changed lives. That evidence is hard for me to ignore.

John Fea is Executive Editor at Current.