What kind of majority rule does democracy require?

As Democrats brood over the difficulties posed by the Senate filibuster, they might take comfort in knowing that things could be far worse for the ruling party. If one of the Senate’s most infamous figures had gotten his way, no political party, however large its majority or clear its mandate, would have the ability to pass legislation without the consent of the opposition. The modern filibuster may be closer to embodying John C. Calhoun’s theory of the “concurrent majority” than anything that existed in his lifetime, but it’s still far short of what he actually wanted.

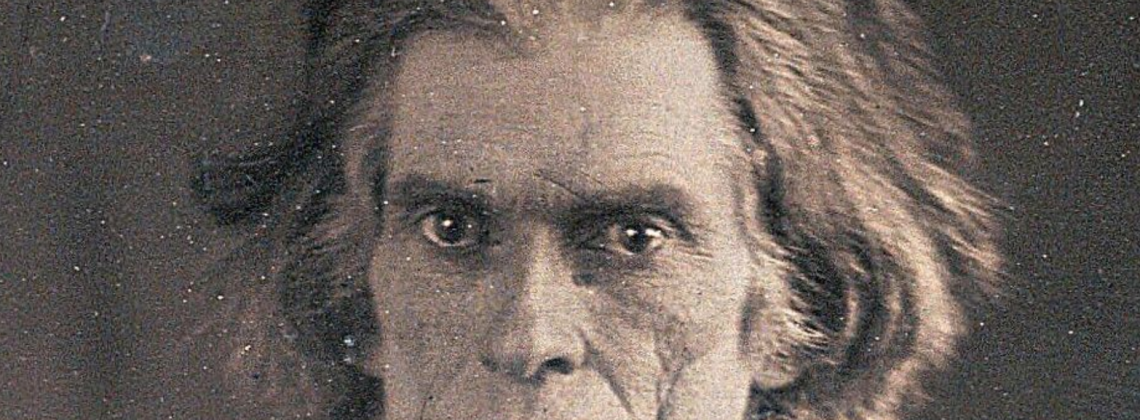

When Calhoun made his final speech to the Senate on March 4, 1850, the proslavery South Carolina senator was dying of tuberculosis. The divide over slavery, he warned, had become so deep that preserving the Union would require a fundamental constitutional change. Predicting that antislavery northerners would soon be in a position to leverage their numerical majority and impose their convictions on the South, and ignoring the long history of southern advantages conveyed by the infamous three-fifths clause, which lent southern states outsized representation based on their enslaved populations, Calhoun called for a “full and final settlement” of the slavery question. The solution he proposed was a constitutional amendment that would “restore to the South in substance the power she possessed of protecting herself” at the country’s founding. Without this amendment, he wrote to his son-in-law a few days later, in a dark mood, “it is difficult to see how two people so different & hostile can exist together in one common Union.” Three weeks later he was dead.

Almost certainly Calhoun had in mind his posthumously published proposal for a dual executive, one from the North and one from the South, each armed with ironclad veto power. The idea flowed out of Calhoun’s long-standing argument that the defining principle of the American Constitution was not majority rule but rather rule by consensus, which he called the “concurrent majority.”

In a famous 1842 speech Calhoun described how the framers of the Constitution had designed the different parts of their creation—the House, the Senate, and the Executive—so as to gather in different ways a sense of the will of the people, and then required the concurrence of all three institutions to pass legislation. Their goal, he claimed, was to win the consent of “the greatest possible number” of the people, a far higher bar than a simple numerical majority. Only this high level of unanimity could put the power of the government into action and convey legitimacy to its actions.

It was no accident that this novel interpretation validated the opposition of a powerful minority: the slaveholding states that Calhoun represented. And yet Calhoun’s argument would not have been effective had it not contained a kernel of truth—evident in the Constitution’s concern for minority opinion as well as its emphasis on consensual decision-making in the very structure of the Senate. It was not for nothing that Calhoun’s enemies often compared him to the eloquent but diabolical figure of Satan in Milton’s epic poem.

Calhoun argued that the founding generation could not have predicted the extent to which, as the country grew, it would become divided into “two great sections, which are strongly distinguished by their institutions, geographical character, productions and pursuits.” Under such conditions the trust, affection, and self-interest that Calhoun believed were the only legitimate forces holding any modern nation together could not survive. The only solution, he argued, was a reconfiguration of the Constitution to revive the lost principle of consensus. “The nature of the disease is such,” Calhoun wrote, “that nothing can reach it, short of some organic change.” That change was the institution of a mutual veto power through the mechanism of a dual executive to give the South complete confidence that it, and slavery, would be safe in the Union.

Calhoun argued that the result of his invention would be political unity, the pursuit of only truly common goods, and a spirit of mutual sacrifice. Acknowledging that on many lesser issues the result of this arrangement would be government inaction, not to say paralysis, Calhoun insisted that on truly crucial measures necessity would force compromise and consent. Republicans, and not so long ago Democrats like Joe Biden, have of course used similar arguments to defend the filibuster.

Thankfully, since it would have meant the preservation of slavery and a fundamental change to the American constitutional system, Calhoun’s idea died with him. But it has had an interesting and unpredictable afterlife. As the political scientist James H. Read has shown, in the mid-twentieth century Calhoun’s description of the mutual veto influenced the theories of Dutch-born political scientist Arend Lijphart, who coined the term “consociational democracy” to describe methods of power-sharing aimed at preserving democracy in deeply divided societies. For a modern example of what a version of Calhoun’s idea might look like, consider the 1998 Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland, shaped in part by Lijphart’s theories. The agreement instituted a “diarchy” that closely resembles Calhoun’s dual executive and required separate majorities of both nationalist and unionist groups to approve important decisions.

The United States is not in need of its own Good Friday Agreement, at least not yet. But as an instantiation of Calhoun’s theory, the comparison with our present situation is illuminating. The filibuster in its current iteration certainly represents a principle that Calhoun would approve, namely the ability of a minority to effectively resist the will of a majority, as long as that majority has fewer than sixty votes in the Senate. But we are still far short of the arrangement that Calhoun actually wanted and, gratefully, from the crisis that precipitated his radical proposal.

And yet one index of our division is how easy it is to imagine history boomeranging back on us. If it does, we will have to answer some of the questions implicit in the fight over the filibuster more directly. Do we still trust one another enough to be governed by what James Madison once called “the first principle of a free Government,” that the majority’s will should prevail? How should we balance the imperative of peaceful coexistence, let alone unity, with the imperative of upholding a principle of American democracy so fundamental that a previous generation went to war to defend it: the principle that the constitutionally expressed will of the people is the ultimate source of authority in our system of government? What are the limits of what we, Republicans or Democrats, should be willing to impose on our fellow Americans by legitimately elected majorities, keeping in mind what Thomas Jefferson once called “this sacred principle, that though the will of the majority is in all cases to prevail, that will to be rightful must be reasonable”?

History cannot answer these questions for us. It can only warn us that we may have to answer them for ourselves.

Robert Elder teaches American history at Baylor University. His second book, a biography of John C. Calhoun, was published in February by Basic Books.

Robert Elder teaches American history at Baylor University. His second book, a biography of John C. Calhoun, was published in February by Basic Books.