Which script were the insurrectionists following?

Our civic life would improve if we all knew more about horror movies. Really.

The last two years have been full of fear. Maybe you’ve noticed.

Horror films shape our fear and are shaped by our fears. Those fears change over time, which is why horror movies featured giant bugs in the 1950s and teen slashers in the 1980s.

Today, fear has become the driving force in American politics. So the ideas and ideals of horror movies (and horror fiction and folklore) become required reading. The more we know about fear, the better we are at facing it. Horror becomes a weird atlas to American life—one that arrives unexpected in the mailbox, smelling faintly of earth, postmarked Elm Street.

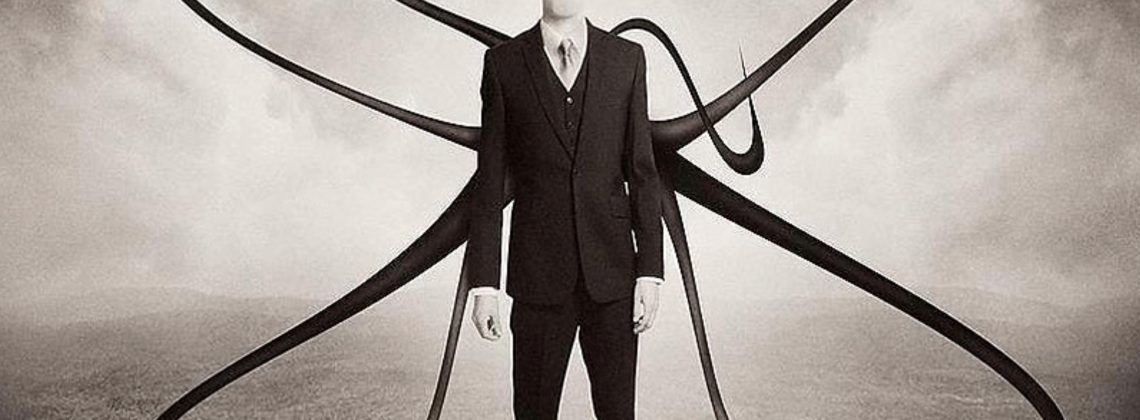

The most important monster of the last twenty years, for example, came out of the internet. On June 8, 2009, the geek forum Something Awful posted a challenge for its fans: Photoshop a creepy picture and write a backstory for it. The user Victor Surge created two spooky black-and-white photos of a faceless man in a suit, with distended arms and possibly tentacles, always in shadow: the Slender Man. Surge added doctored documentary evidence for his creation—photos, newspaper clippings, children’s drawings. Other users joined him, and by the end of the month a huge archive existed where none had before. In May 2009, the Slender Man did not exist; in July 2009, he was part of recorded history. The Slender Man rabbit hole is filled with a trove of manufactured documentary evidence, all of it partial, all inviting explanation. It is a mystery and an activity and a horror story all at once: the world’s first crowdsourced monster.

Slender Man crawled out of Something Awful and into popular culture. Outside its original forum, the pseudo-documentation of Slender Man looked more real (as it was designed to). Even Surge was shocked; anyone, he said, could see its origins in a “very public Something Awful thread. But . . . despite this, it still spread.” The bric-a-brac nature of the material reminded users of other urban legends—Bigfoot, the Loch Ness Monster, chupacabras—but with more sinister intent. Sometimes he killed kids. Sometimes he got other people to do the killing for him. In 2014, two young girls in Wisconsin murdered another child in the belief that Slender Man told them to do it.

Horror fiction, real murder: Slender Man lives both in media and in reality. His very essence blends folklore and fact. He is frightening because he is supposed to be real. The confused babble of evidence on the internet acts like an archive of information, even though it’s fabricated.

Found footage films in the last twenty years follow the same logic. Blair Witch Project made hundreds of millions of dollars with a movie that looked like amateur filmmakers shooting on a camcorder—which it was. The horror came because the film insisted this story of an unknown force stalking kids in the woods was real. Audiences flooded to theaters to see for themselves. Blair Witch also put evidence into cyberspace: For a year after the film, the actors’ IMDb pages read “Missing, presumed dead.”

So too with the Babadook, who lives in a children’s book and in the basement, or the 2016 creepy clown scare, which began as a Wisconsin hoax that produced real police warnings and panics. These monster stories are interactive—you are supposed to look for clues, debate them, and scare yourself. Figuring it out is part of the story.

And in that sense, the most successful horror story of 2020 is QAnon.

QAnon—the now-infamous ideology that holds that Donald Trump and a few allies are confronting and defeating a secret worldwide cabal of Satan-worshipping pedophiles—is a horror story. The monsters are demonic men and women who control all media and most governments. They seek to enslave and destroy, and can only be defeated by the Word of God. Average Americans who know the truth are the last chance to destroy the monsters and save humanity.

Like the Slender Man, the legends and lore of Q are manufactured on the internet; like the Slender Man archive, there is a wealth of evidence. Q enthusiasts ask people to “figure it out for yourself.” The movement’s hallmark is the insistence that people “connect the dots,” bringing together seemingly innocuous evidence that when properly assembled shows the full nature of the horror—much in the same way that Shining fans plot the impossible architecture of the Overlook Hotel. But The Shining is a movie, and QAnon is a political philosophy that drives seventeen percent of the American population.

I don’t need to describe QAnon; it is well-documented here and here.

But QAnon is too often described as a “conspiracy theory,” akin to the nutty but harmless idea that NASA faked the Apollo moon landing. QAnon is more than a conspiracy theory—it’s a horror movie. It’s the story of desperate humans fighting demonspawn to save the world.

(Deep cut for nerds: remember when Roddy Piper fights Keith David to make him put on the glasses in They Live? QAnon believers think they have found some glasses, and so they will try to beat up the rest of us.)

QAnon and anti-government extremists now in the mainstream have absorbed the traits and assumptions of other horror movies of the 2010s—the apocalypticism and desperation of The Walking Dead, the assurances of Stranger Things and Cloverfield that the government is both well-funded and anti-citizen, to say nothing of the Christian allegories in the bestselling Left Behind series. QAnon believes it is fighting a monster apocalypse—and as most zombie films tell us, in a catastrophe, all bets are off. To them, America is in a survival horror movie, and, therefore, anything goes.

And from there to January 6—which looks horribly like a reel of found footage film.

As long as we treat QAnon and related misinformation as “conspiracy theories,” we will keep being shocked at their disdain for truth. Millions of Twitter accounts will keep posing unhelpful questions about why adherents still believe Q when it is demonstrably true that the 2020 election had no fraud, and that John F. Kennedy Jr. is still dead.

Part of the reason is that QAnon believers and other armed anti-government insurrections aren’t making a reasoned political argument—they are living out a horror story. Giving them the facts is important, but not sufficient.

There is something else we must explain to the QAnons—and more importantly, to folks who might be swayed by their arguments. We need to remind them that life doesn’t have to be a horror movie. Indeed, it’s good not to be in a horror movie. You have to be able to turn the movie off, which means getting off social media, turning the phone to silent, and getting out in the real world. The one character who almost never appears in horror is the patient, civically-minded citizen who works hard to address real local problems. She doesn’t show up in horror because she is the antithesis of horror. Patience, respect, and the common good usually are not terribly scary. That is where we want to be politically, and it’s a good first step to unwriting this horror story.

Adam Jortner is the Goodwin-Philpott Professor of History at Auburn University. He is the author of The Gods of Prophetstown and the Audible original series American Monsters.