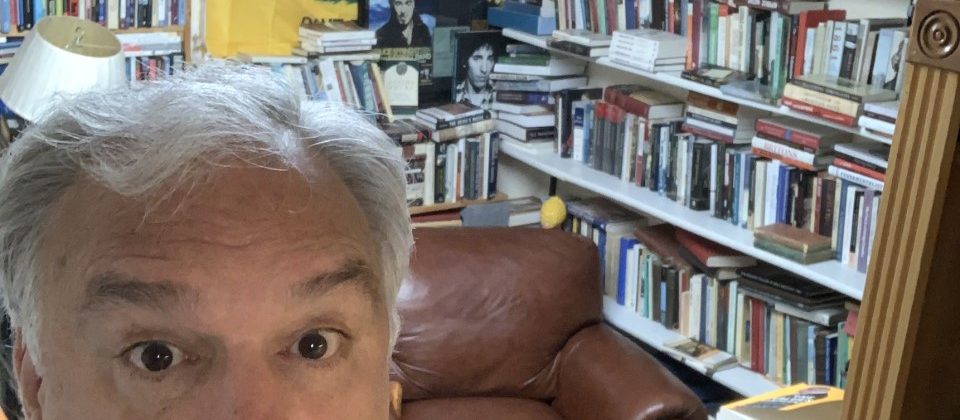

It’s around here somewhere. Or wait, maybe it’s at the office. Do I drive to campus or just see if I can find the excerpt I need online?

Yes, I know there are cataloging programs for this, but I just don’t have the time to catalog every book I own. One day I am going to have to pay someone to do it.

Until then, I will continue to read people like Mark Athitakis. Here is a taste of his piece “Why bother organizing your books? A messy personal library is proof of life”:

The late French essayist and novelist Georges Perec understood the anxiety of shelving. In his 1978 essay “Brief Notes on the Art and Manner of Arranging One’s Books,” the title work of a newly issued collection, Perec’s discussion of the many schemes for handling your personal library only shows how utterly impossible the task is. You could, for instance, agree only to keep 361 books in your library — buy one book, get rid of one. But then, he writes, you’d have to decide what a “book” is. Is a three-volume series one book or three? Maybe it’s better to stick with 361 authors instead of books. But then some books are anonymous, and some books don’t make sense without others in the same genre, and . . .

Perec died in 1982. His home library contained more than 1,800 books.

Perec’s essay is somewhat tongue-in-cheek — he was an Oulipian, a tribe of literary gamesmen who found creativity in extreme restraint. (He’s probably most famous for his 1969 novel, translated into English as “A Void,” in which he avoided using the letter E.) But however deep the joke runs, he knew he was writing about a legitimate crisis — not so much one of shelving as of personal identity. How much mess will we accept in our lives? How much order? Shelving, he notes, exemplifies “two tensions, one which sets a premium on letting things be, on a good-natured anarchy, the other that exalts the virtues of the tabula rasa, the cold efficiency of the great arranging, one always ends by trying to set one’s books in order.”

Perec runs through a number of ways to address that good-natured anarchy. We can categorize books alphabetically, that old standby, but also by continent, color, publication date, genre and more. But all methods, he insists, are doomed to failure. That’s partly because any one book has so many different ways to be uncooperative. Sometimes a book rebels via size. (Where do I put Chris Ware’s “Building Stories,” published in a board-game-size box?) And increasingly, shelving by genre is a headache (Where does the autofiction go? Or genre-blurring novels like Victor LaValle’s “The Changeling”?).

And, of course, books move, drifting from living room to office to the floor as we use them. In truth, the only library that can truly satisfy our sense of order is one you never touch. And there’s a market for that: The Strand bookstore in New York will sell books by the foot for people who want bespoke-looking shelves without going through the rigmarole of choosing (and presumably reading) a book. (You can choose by color, style or subject.) Books do furnish a room, as the English novelist Anthony Powell put it, but a living library is determined to look like a couch the cat scratches.

Read the entire piece here.