The truth about race is out there. And it doesn’t take an academic theorist to see it.

In the wake of the greatest year of racial unrest in the United States since 1968, governors in Idaho, Oklahoma, and Tennessee have signed bills banning the teaching of critical race theory in public schools. State legislatures in Oregon, Arkansas, Utah, Missouri, Arizona, Ohio, Georgia, Texas, Iowa, Louisiana, New Hampshire, Kansas and West Virginia have either passed, or are in the process of debating, similar bills.

The argument over what public school students should learn about race is the latest front in the culture wars. Much of the battle centers on the teaching of American history.

So how should you, as a history teacher, respond to these new mandates forbidding the teaching of critical race theory in the classroom? For starters, here are a few things to remember:

First, most politicians who oppose critical race theory have no idea what it is.

Second, most politicians who oppose critical race theory aren’t intellectually curious enough to learn more about it. Why should they read critical race theory when they can simply use it as a bogeyman to maintain power and advance their political careers?

Third, most politicians who oppose critical race theory are clueless about what actually happens in an American history classroom—and they have no real interest in hearing what you might tell them about what happens in an American history classroom.

So let the politicians have their way. Take “critical race theory” out of your lesson plans and just keep teaching American history.

This will require you to show students that racism has always been an ordinary and common part of everyday life in America. Teach them about the Middle Passage, the tobacco fields of colonial Virginia, the rice fields of colonial South Carolina, and the links between the happiness of Pennsylvania grain growers and the oppressive slave regimes on the West Indian sugar islands.

Introduce your students to the voices of enslaved writers and activists like Frederick Douglass, Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey, Harriett Tubman, and Harriet Jacobs. These men and women have stories to tell that will reveal the daily racism they encountered in the antebellum South. As a history teacher, you know the value and the power of a primary source.

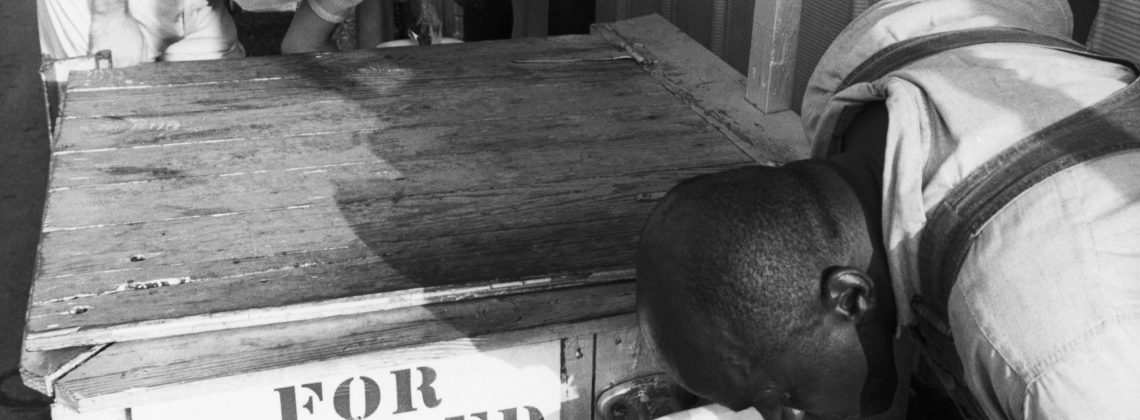

And don’t forget to examine the legacy of Jim Crow laws and segregation. Familiarize your students with redlining in American cities. Read the speeches of the civil rights movement. I know you are already doing this. But always remember: It will be hard for your kids to study these things in your American history class and not come away with the idea that discrimination is built into our institutions and legal codes.

As you uncover these stories in American history, your students will realize that racial injustice helps white people and harms people of color. Show them that because white people benefited from racism many of them did not have the incentive to do anything about it. You don’t have to insult your students’ intelligence by preaching this to them. Just teach the facts in context and explain how those facts are related to one another over time. Instruct them how to see continuities between the past and the present. Do what you were trained to do.

Make sure your students understand that the racial categories we use today are not biologically determined but invented by human beings. There is nothing inherent about any race that should lead to its oppression. The study of American history should lead them to see how men and women in power constructed the idea of racial difference and promoted bigotry based on those differences.

For example, you probably begin your American history course with colonial America. In seventeenth-century Virginia, the white men in political power constructed a social system that made Africans, based on the color of their skin, a permanent, enslaved underclass. The House of Burgesses passed laws that defined Black men and women as slaves for the purpose of quelling disgruntled poor whites (former indentured servants) who had a propensity for social and political rebellion. The codification of race-based slavery in Virginia law resulted in the social, economic, and political advance of these marginalized white colonials.

These decisions had long-term consequences for how white people treated people of color in the decades and centuries that followed. They raise important questions about the meaning of words such as “liberty” and “freedom.”

Were there individual acts of racism in colonial Virginia? Of course. But what the Virginia government did was systemic—its leaders embedded racism in the culture of the settlement. As many of you already know, the historian Edmund Morgan made these arguments about colonial Virginia nearly fifty years ago in a book called American Slavery, American Freedom. He wrote at a time when critical race theory was barely in existence.

Point your students to similar moments in our past where white people were able to achieve something called the “American Dream” on the backs of slaves and other oppressed and marginalized people.

Finally, teach your students that the people they study in the past have multiple identities that when taken together make them whole people. Americans have always engaged the world through the prism of racial identity, but they have also acted based on their religious beliefs, social class, gender, political convictions, sense of citizenship, and family or tribal considerations, to name a few. Historians understand the complexity of the human experience and the ways different identities overlap and intersect.

I imagine that you did not read much critical race theory during your undergraduate training as a history teacher. Don’t worry about it. You didn’t miss much. Your students don’t need highfalutin academic theorists or power-hungry politicians to see how racial injustice was embedded in the history of the republic. Just teach them to study the documentary record with their eyes open. They will notice that racism is not some kind of aberration practiced by a few “bad apples.”

Don’t teach “critical race theory.” Teach good American history. Let the politicians play their games. Your job is to teach students how to think about the past in all its fullness.

John Fea is Executive Editor of Current.