Without accountability, the national slate doesn’t get clean—no matter how often we try to wipe it

On a chilly winter morning in 2017, I struck up a conversation with the Uber driver en route to the airport. He explained that he had migrated from Ghana, so I asked for his impressions of America. He paused for a moment to collect his thoughts. “The thing about America,” he said, “is that it suffers from historical amnesia.”

The observation struck me. It got me thinking about how contentious our national discourse around even basic elements of our history has become. For every 1619 Project probing the legacy of race-based slavery, there is a 1776 Commission seeking to extract the nation’s pristine ideals from history’s unseemly details. I eventually concluded that historical amnesia is a feature, not a bug. And it is tied to the powerful restorationist currents in American history and life.

In a Protestant context, restorationism seeks to recover a form of religious practice that reflects the values, experiences, and outlooks of the earliest Christians. In secular form, it manifests in the push to align the present with an idealized past. In both iterations, it offers a fresh start and a chance at redemption. It was these traits that attracted settlers to the British colonies, inspired the formation of the United States, and propelled America to global leadership. It is no exaggeration to state that without a pronounced restorationist impulse America as we know it would not exist.

But restorationism also has a shadow side. It can tempt us to overlook vast swaths of our history, particularly the ugly parts. When misused in this way it induces historical amnesia. As a nation, we are practiced at tuning out those who warn against restorationism’s misuse. But we ignore such voices at our peril. To make good on America’s restorationist promise, we must find the courage to confront our historical amnesia and correct the misuses of restorationist motifs that perpetuate it.

Before disembarking on New England shores in 1630, Puritan minister John Winthrop charged his fellow shipmates with the labor of building an exemplary “city upon a hill.” Their model Christian community would inspire what they saw as desperately needed religious reform in England. Once this process was underway the colonists would pack up and sail home. This restorationist “errand in the wilderness” was supposed to be temporary.

Things did not go to plan. By 1636 Massachusetts Bay Colony suffered its first major schism when it expelled a minister named Roger Williams. He formed his own restorationist community in what today is Rhode Island and founded the first Baptist church in North America. The colony’s example also failed to catalyze the kind of religious reform back in England that Winthrop and his fellow settlers had hoped for. In time they came to terms with the fact that their “errand in the wilderness” would be permanent. But as restorationist communities proliferated throughout the colonies and the Puritan “errand” gave way to the American Experiment, it became clear that the new nation would always strive to be that “city on a hill.”

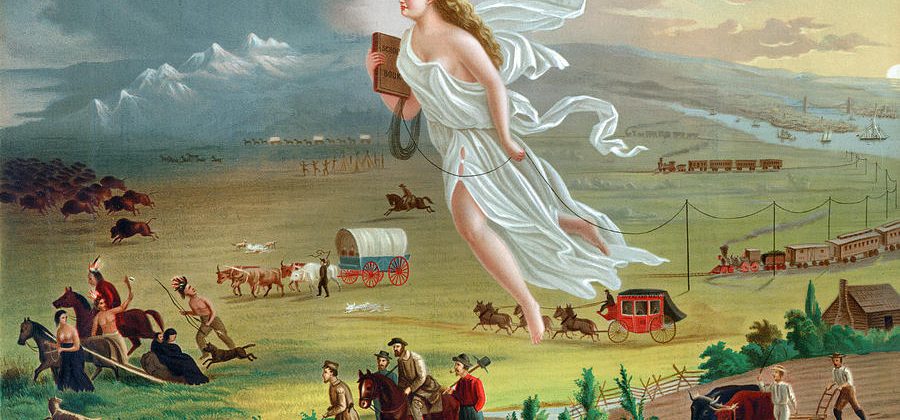

This image brings the paradox of America into focus. On one hand, its promises of freedom, opportunity, and fresh starts have attracted migrants from across the world. These newcomers, in turn, helped transform America into the most powerful and prosperous nation in history. In this regard, the restorationist impulse has served America well. But how does a nation of redemption-seekers build a chattel slavery economy? Massacre Native Americans? Birth Jim Crow? Force Japanese Americans into internment camps? Exploit the undocumented? Oversee a massive prison-industrial complex? And despite it all, still see itself the city on a hill?

One crucial element of this self-delusion is that, as a nation, America has untethered restorationism from accountability. To understand this dynamic, it is worth understanding why restorationist narratives capture the American imagination to begin with.

The appeal of restorationist narratives rests on the prospect of redemption. Take, for instance, a trio of quintessentially American religious movements. Pentecostalism promises direct, unmediated contact with the transforming power of the Spirit. Fundamentalism aims to uncover and restore a faith’s true foundations. The Prosperity Gospel claims to harness spiritual power to secure material prosperity. Each offers healing, transformation, a second chance—the opportunity, in short, to find redemption. The restorationist ethos so saturates our cultural atmosphere that one need not be religious to absorb it. The entire self-help industry, for example, trades on the notion that we can always, in some sense, start over and do better.

What does restorationism have to do with historical amnesia? The restorationist impulse risks giving the impression that our personal histories are analogous to a slate that we can clean whenever we want. This, in turn, suggests that in the end our triumphs matter but our mistakes do not. But can the consequences of our actions be so easily brushed aside? A person who admits to drinking too much and asks forgiveness from their spouse might benefit from a second chance. Simply asking for forgiveness, however, does not mean that the second chance will be offered; that is for the spouse to decide. The spouse may make the second chance conditional upon getting counseling, joining a twelve-step program, or avoiding certain kinds of social situations. To redeem themselves, the offending party must accept accountability. And the offended party has a say in determining what accountability looks like. Without a corresponding emphasis on accountability—on owning up to past mistakes—the promise of continual fresh starts will only entrench the problem.

This same pattern can play out on a national level. As a nation, the restorationist impulse has spurred us to attempt and accomplish great things. It also tempts us to celebrate our triumphs while overlooking our failures. Many of us have become so habituated to thinking we can wipe the national slate clean at will that we’ve lost sight of our mistakes; we bristle when they are brought to our attention. Instead of turning to history to hold us accountable, we choose historical amnesia. And when we do, it is always the vulnerable, the powerless, and the wronged who pay the price.

Today, the restorationist impulse is as strong as ever. Consider MAGA with its promise to restore American greatness, or Biden’s forward-looking charge to Build Back Better. But if we aspire to be the shining city on a hill, we need to own up to our mistakes, not ignore them. Winthrop made as much clear immediately after he invoked that powerful image:

The eyes of all people are upon us. So that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken, and so cause Him to withdraw His present help from us, we shall be made a story and a by-word through the world. We shall shame the faces of many of God’s worthy servants, and cause their prayers to be turned into curses upon us till we be consumed out of the good land whither we are going.

To avoid this fate, we too must hold ourselves accountable and be willing to be held accountable by others. And it begins by confronting our historical amnesia.

Jeremy Sabella lectures at Dartmouth College and is the author of An American Conscience: The Reinhold Niebuhr Story.