René Padilla’s life reminds us what it means to be whole

On April 27, 2021, Carlos René Padilla, the Latin American theologian whom Christianity Today calls the “father of integral mission,” died. He was eighty-eight years old.

Born in Quito, Ecuador and raised in Bogotá, Colombia, Padilla attended Wheaton College as an undergraduate and took a doctorate in New Testament from the University of Manchester. After 1967 he lived in Buenos Aires, but he was truly a citizen of Latin America. He gave himself to the leadership of a remarkable array of organizations throughout the continent, including the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students, the Latin American Theological Fellowship, the Kairós Foundation, Tearfund, and the Micah Network.

In all of his work Padilla insisted that the confrontation and transformation of social structures that foster injustice—and all manner of evil—must be part of the Christian mandate. This was what he and his friends meant by misión integral, or, as it has often been translated in English, “holistic mission,” a theological vision that Padilla and others of the Latin American Theological Fellowship nurtured and propounded. They took up this project as Liberation Theology was flowering throughout Latin America, and this parallel development caused great concern among some evangelical gatekeepers. Their concern was heightened by the influential role Padilla and other Latin American theologians played in the development of the Lausanne Covenant of 1974—a crucial moment in the evolution of worldwide Christian mission.

Among the concerned was the editor of Christianity Today, Harold Lindsell. In 1976 Lindsell wrote to Padilla inquiring of the latter’s “attitudes toward socialism, capitalism, free enterprise, property, revolution, class struggle, etc.,” as Padilla would later summarize it. In his response to Lindsell, Padilla declared that he was not a Marxist, that a “socialist ideology” was “not the answer that the Third World needs.” But neither did he think capitalism an adequate response. “It is leading the West to destruction,” he contended, “and offers no hope for the Third World.” In pursuit of an alternate way, Padilla opined that “both the myth of growth and the myth of revolution must be debunked. We Christians,” he told Lindsell,

should be the first in working toward the creation of new structures which will cut across the socialist/capitalist dichotomy and offer man a more human life. Unfortunately, we lack the faith and courage to be that. We find it easier to take refuge in one of the two myths, which we then try to dress up in biblical language.

Reading editorials Padilla wrote between 1982 and 2002 for the magazine Misión, it’s evident that he was aiming to develop, as he put it, “a means God could use to incite within the evangelical people a biblical concept of Christian mission.” An essay on the ethics and stewardship of material goods would turn into one of the chapters of his 2003 book, Economía Humana y Economía del Reino de Dios (“Human Economics and the Economics of the Kingdom of God”). Note his opening premise: “Economics, like all of the human sciences, has an ethical dimension the definition of which must not be left only in the hands of those who specialize in economics.” Observing that ideological commitments shape a large portion of human decision making, he proposed that the biblical ideals of justice and solidarity become a fundamental part of the decision-making process in all social spheres, including economics.

Padilla questioned market fundamentalism and the absurd, ever increasing concentration of wealth in our day, the lethal shape of which the pandemic has thoroughly revealed. 87% of those vaccinated are in wealthy nations, while in the less developed nations the percentage drops to .2%. According to Businesswire, as of April 1, 2021 “high-income countries have vaccinated on average 1 in 4 people, whereas only 1 in more than 500 people in low-income countries has received a COVID-19 vaccine.”

Since it is only a living solidarity that will enable us to overcome this crisis, this inequality is grave in an especially disturbing way. There is no way out of the pandemic exclusive to particular persons or classes. In this moment we need to act on the reality that we are all equal and then embrace this fact in a way that we never have before in these, our unequal societies.

Through his everyday presence Padilla affirmed the importance of community life and the work of the local church. While he stressed the priority of intellectual and theological reflection, he emphasized (as he put it in the editorial of the first edition of Misión, in 1982) that these must occur “not as ends in themselves but rather as necessary means in the service of our Lord Jesus Christ, to whom belongs the glory and power forever.”

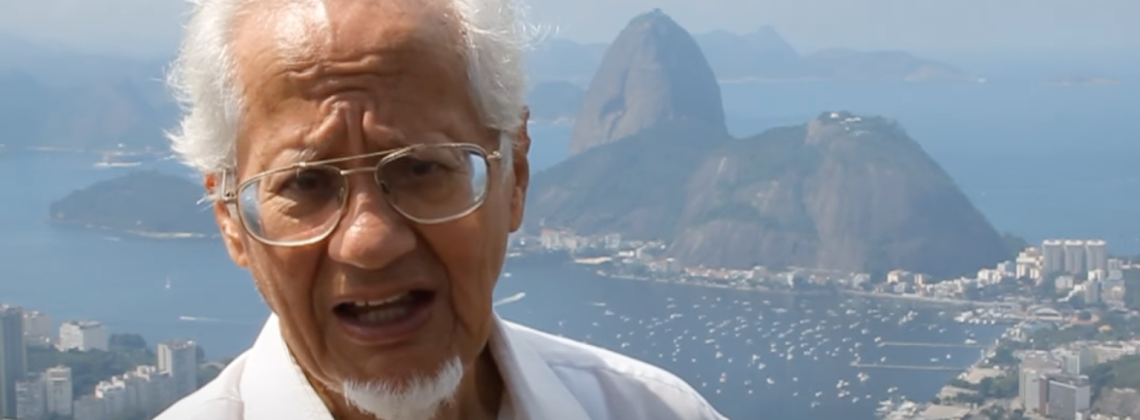

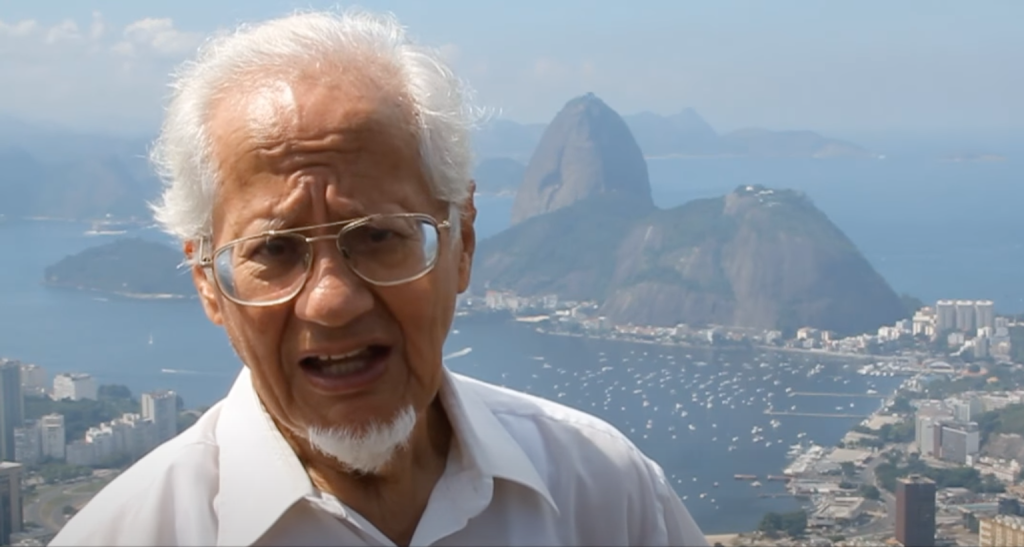

More recently, after participating in a meeting in Brazil, Padilla—touched by the testimony and activism of some Brazilian leaders who had approached racism from the perspective of black theology—renewed his interest in the issue of racism. A friend reminded me that as a member of the Lausanne Congress in 1974 Padilla had made racism a central concern, as this passage from his address shows:

The gospel of culture-Christianity today is a message of conformism, a message that, if not accepted, can at least be easily tolerated because it does not disturb anybody. The racist can continue to be a racist, the exploiter can continue to be an exploiter. Christianity will be something that runs along life, but will not cut through it.

A truncated Gospel is utterly insufficient as a basis for churches that will be able “to generate their own Calvins, Wesleys, Wilberforces and Martin Luther Kings.” It can only be the basis for unfaithful churches, for strongholds of racial and class discrimination, for religious clubs with a message that has no relevance to practical life in the social, the economic, and the political spheres.

The issue of race is cruelly visible in Brazil, of course, but it is equally terrible, violent, and alienating throughout the Americas, as well as other parts of the world. Our histories as slave societies, and the prejudice and inequality that persist today, bore in Padilla a desire to work alongside others on a book dedicated to this theme. It is a project we in Brazil intend to continue, as matters of race and ethnicity have been, in my view, something of an omission in the work done by those associated with holistic mission.

In his preface to Mission Between the Times: Essays on the Kingdom, Padilla expressed his hope that his writing would contribute, in a “small way toward turning the face of evangelicalism in the direction of a suffering world.” He described himself as “a highly privileged witness to what the Spirit of God has been doing to give his people a renewed sense of holistic mission.”

Thirty-six years after the publication of this book, there is no doubt. Through his seminal theological work and his transformative way of life in his working-class neighborhood, René Padilla has made an enormous contribution to the work of the Gospel in this world. Today we can praise God for his truly integral witness, a response to God’s call that will bear fruit for generations to come.

Alexandre Brasil Fonseca is a sociologist and Associate Professor at the NUTES Institute for Science and Health Education at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and the author of Evangélicos e Mídia no Brasil (Evangelicals and the Media in Brazil, 2003). From 2012-2016 he was special adviser to the President of Brazil on religious affairs. He is the president of Peace and Hope Brazil. Contact: abrasil@ufrj.br