A hidden history lurks in the images featured in PBS’s The Black Church. Why didn’t its creators tell it?

About twenty minutes into the sweeping four-hour PBS documentary The Black Church: This is Our Story, This is Our Song, Henry Louis Gates Jr. describes the emergence of the “invisible institution” of the Black church in the United States: the secret gatherings of the enslaved to worship in their cabins, in the woods, or down by the riverside. As he and his guests laud the persevering devotion of eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Black Christians, black-and-white images float across the screen.

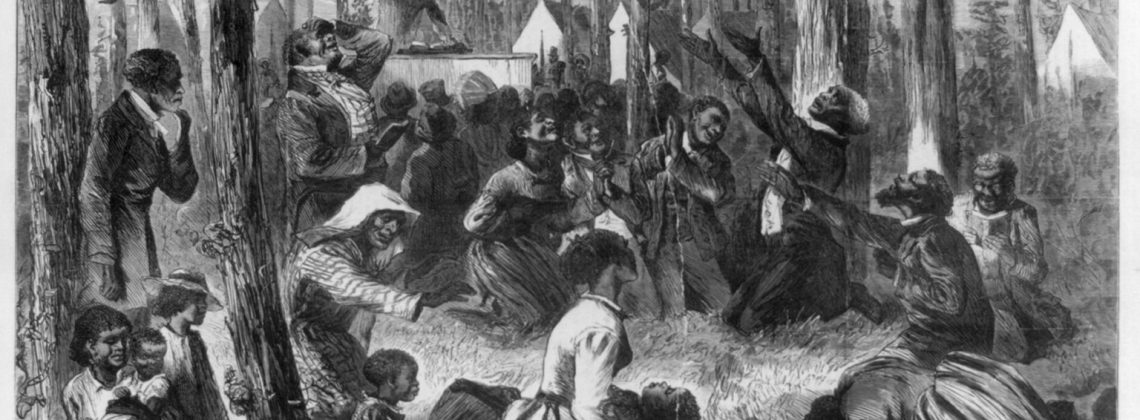

At first blush, the images neatly fit the voice-over narration. We see the Black worshippers piled together in dimly lit spaces, hands raised and mouths open in song. We zoom in on a Black preacher with outstretched arms. Men, women, and children kneel in prayer in a forest clearing. The images look like woodcut prints; crisp black lines wrap around bodies and the varying density of intersecting lines suggests depth. We identify them fairly easily as historical images rather than modern graphics. In the context of the episode, they function as documentary: they assert themselves as period illustrations of the events being described.

As a viewer, I appreciate the show’s efforts at conveying the richness and complexities of the Black church in America. But as an art historian, I mourn the missed opportunity to treat the images themselves as part of this history.

One image in particular underscores the loss I sense, as well as the missed opportunity: an image of Black worshippers in a forest. It first appears while historians Larry G. Murphy and Barbara D. Savage describe how the enslaved created a spiritual world that was “sustaining to them, though it needed to be kept secret.” As an actor reads former slave Emma Tidwell’s account of clandestine worship practices, we see a dark-skinned man with snow white hair lifting his palms to the sky as he kneels in a clearing. Then we cut to a view of a Black woman in a long dress sitting on the ground and leaning forward as a child sleeps in her lap. To the left, a young Black girl seems to mimic her posture. We cut again to a Black woman kneeling prostrate on the ground, and then pull out to see the image as a whole.

Where does this image itself come from? Like many of the other black-and-white graphic images used in the mini-series, this print was originally published in Harper’s Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. Harper’s was one several extremely popular illustrated magazines in the U.S. in the nineteenth century, filled with news, opinion pieces, fiction, and humor alongside numerous woodcut illustrations. The image described above accompanied an anonymously written article entitled “A Negro Camp Meeting in the South” in the August 10, 1872 edition—more than five years after the formal abolition of slavery.

The article begins by claiming that although American life is “usually devoid of the picturesque,” religious camp meetings can provide “food for the imagination.” He credits this to the “negro mind” and its “insatiable craving for excitement.” The author then goes on to describe his experience of cultural tourism for his anticipated white audience. The illustration, he says, accurately portrays the threads of seeming “desecration” and “true devotion” in Black worship. While the gray-haired old man is “no pretender,” the women are more suspect. The young girl on the left becomes for him a “pickaninny” munching on cornbread, learning to imitate the “coquettish damsel” whose religion is, to the author, mere posturing.

The article continues to traffic in racist stereotypes while condescendingly praising the charm of the event. Its closing sheds light on the vulnerability of the Black church even after Emancipation: The author is forced to flee from the meeting because a “group of roughs” had come to break up the gathering and were attacking the worshippers.

Thus, the producers of The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song use a post-Emancipation woodcut print intended as exotica for a white audience as an unironic illustration of Black subversion and perseverance in the midst of slavery.

Curiously, the documentary gives no indication that the image was actually made decades after the practices being described, or that the print was intended to discredit the very institution the mini-series is honoring. Of course, one might argue that this was a purely practical choice for a non-specialist, television audience. We do not have extant images that depict the secret worship practices of the enslaved, after all, so woodcuts from Harper’s necessarily fill a void. We generally accept this kind of substitution because we expect images to function as illustrations of the past; the pictures are there to explain the text. But treating historical images as mere symbols hinders our historical understanding in at least two ways.

First, it glosses over stories of absence. If we do not have direct visual accounts of an event or community, we must ask why that absence exists. The lack of art, among other forms of self-representation from the early days of the Black church, is a result of its oppression. It is a reason to grieve. Rather than concealing this absence we should address it honestly and responsibly. Perhaps this means commissioning contemporary artists or designers to make new work that interacts with the historical narrative. Perhaps this means leaving a screen or part of a museum display intentionally blank, with only silhouetted shadows. At the very least, it demands that we announce when an image is used anachronistically and that we call attention to the reasons for a void.

Second, turning historical images into symbols causes us to miss the larger story of which the image is a part. Regarding an image like this one from within its own original context adds more texture to the history of the period. An illustration published in a magazine and seen by thousands in late-nineteenth century America played a powerful role in shaping the audience’s perception of the depicted occurrence and community. The truth is that the Harper’s illustration taught its original readership that Black women are conniving, that Black Christians are driven by mindless emotions, and that the Black church can provide charming entertainment for whites.

At the same time, the image’s destructive original function does not foreclose better possibilities for its use. Indeed, there is something thrilling about Black historians narrating church history with awe and affection for their ancestors, thus reshaping how today’s viewers understand the past. But in order to realize the richness of this counter-reading, we must know what we are reading against.

Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt is Associate Professor of Art and Art History at Covenant College in Lookout Mountain, GA.

Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt is Associate Professor of Art and Art History at Covenant College in Lookout Mountain, Georgia, and she is the author of Redeeming Vision: A Christian Guide to Looking at and Learning from Art (Baker Academic, 2023). She is a Contributing Editor for Current.