In the pandemic, Brazil and the U.S. share a dubious leadership. Evangelicals in both nations do, too.

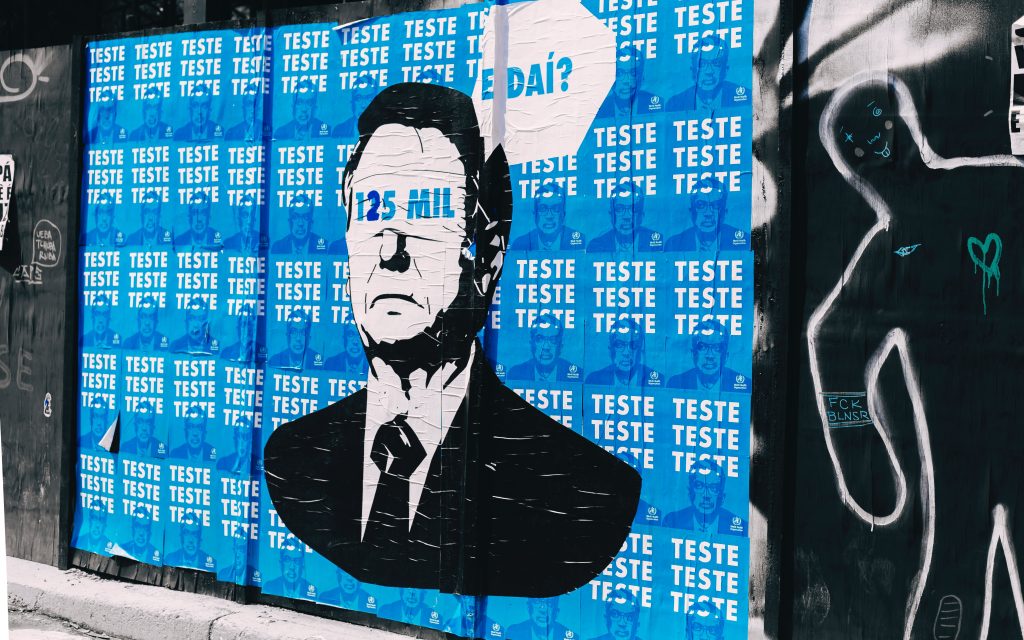

The United States and Brazil lead the world in one area, and it is a sad triumph. They stand at positions one and two in the number of COVID-19 related deaths. Comprising only 6.9% of the world’s population, they are responsible for 30.5% of deaths from the disease. This is due in large part to the erratic, denial-based stances of their presidents—or in the case of the United States, its past president.

The approach to the pandemic of Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro and the United States’ Donald Trump stems from their political style: authoritarian populism, with its polarizing tactics. Such leaders prefer to create new problems rather than resolve old ones, basing their messaging on lies, irrationalities, and symbolic violence. During the pandemic many held out hope that the conduct of Bolsonaro and Trump would change. But they stayed true to their elemental political style. As the philosopher Alex Demirovic puts it, in a moment of crisis authoritarian populists elect not to solve problems but sow division. The refusal to make concessions is their trademark, and the constant spawning of moral panic—over immigration, sexuality, public security, Order, the family, Traditional Values—charges their speeches and animates their followers.

Today, when much of the world is experiencing enlarging hope due to the advancing rates of vaccination, Brazil finds itself facing the opposite direction, with the threat of new variants and a rising number of deaths. (See graph 2.) While the actions of Joe Biden seem to have shifted the fortunes of the U.S., Brazil is left, alas, with Bolsonaro, the “Trump of the Tropics on steroids,” as one Latino theologian told me while I was visiting Pasadena in 2018. In his denial-based, science-defying crusade, Bolsonaro is now left without his American partner.

Examining the support Trump and Bolsonaro each attracted during the pandemic takes us to the extremely varied sector classified as “evangelical.” Evangelicals, who now make up about thirty percent of Brazil’s population, are among Bolsonaro’s strongest supporters, just as in the United States they’ve placed themselves squarely behind Trump. Three of Bolsonaro’s cabinet members are evangelical pastors, and a range of evangelical media, political, and denominational agencies have given him their seal of approval.

The Lutheran theologian Rudolf von Sinner has identified three interpretive stances Brazilian evangelicals have taken amid the pandemic. The first is punitive, understanding the global crisis as divine punishment, in the same eschatological lineage as the Genesis flood. The second group holds a view Sinner dubs “magical”: they deny the gravity of the situation and cling to facile solutions, in the face of tens of thousands of health professionals, public officials, and scientists seeking to address it. The third group has taken a more responsible position, understanding the need for cooperative action in the face of catastrophe.

Recent statistics released by the polling agency Datafolha underscore just how far Brazilian evangelicals have distanced themselves from the rest of society. While 6% of Catholics and 3% of Spiritists say they will not be vaccinated, the percentage of evangelicals who claim they will decline vaccination is 14%. When asked about restrictions on public gathering places, a majority of evangelicals—59%—are against the closing of churches, even as they follow the Brazilian mean—30%—in opposition to restrictions on other public venues.

At this moment Brazil leads the world in COVID-19 related deaths. Of all the deaths that occurred during the month of March, 37.9% took place in either Brazil (24.1%) or the United States (13.8%). In Brazil, the overwhelming sadness of this past month reveals itself in yet more statistics. 66,573 people died due to the virus, twice the total of the previous highest month, July 2020. Whereas throughout the world one in ten of the total number of COVID-19 deaths occurred in March alone, twenty percent of Brazil’s total number of COVID-19 deaths occurred in March. That total is larger than the sum throughout the entire pandemic of deaths in 109 countries, the combined population of which is 1.6 billion, over against Brazil’s 212 million. On March 31, one in three COVID-19 deaths in the world took place in Brazil: 32.9%. According to the economist Marcos Hecksher, the risk of dying in 2020 from COVID-19 was 3.6 times higher for people who lived in Brazil than in the rest of the world.

In the midst of this chaos, mayors and governors, faced with the absence of any national program, put into place a series of restrictions on social movement for ten days at the end of March and the beginning of April. In the midst of these efforts, the National Association of Evangelical Jurists (ANAJURE) took a case against the prohibition of in-person religious services to Brazil’s Supreme Federal Court, arguing that it was a violation of religious liberty. To the surprise of many, on the Saturday before Easter a single member of the court issued a temporary injunction in support of the evangelical jurists and authorized the opening of the churches. Its rationale explicitly followed the lead of the U.S. Supreme Court.

In January, Australia’s Lowy Institute assessed the pandemic performance of ninety-eight countries. The United States was 94th. Brazil came in last. When the institute updated its ranking in March, this time with 102 countries, the United States was 96th, while Brazil, along with thirteen other countries, was excluded from the ranking due to the lack of reliable data—which is, of course, a serious problem in the midst of the disinformation epidemic we are also suffering. Studies suggest that the actual number of COVID-19-related deaths is much higher—a reality intentionally obscured by what one group of scholars has recently dubbed a coordinated “institutional strategy for the spread of coronavirus” executed by the government of President Bolsonaro.

Professor Todd McGowan offers insight at the level of political economy that can help us better grasp this massive, apparently inexplicable situation. Amid disasters such as this, the deep and costly “misalignment” between the state and capital is exposed, he argues, and in ways that make evident its gravity and tragedy. In ordinary times the state preoccupies itself (with only apparent impunity) with attending to the interests of capital. But in the midst of a natural disaster and the dying of millions, the reality that we are creatures who need to live in community becomes finally and painfully clear. The experience of social distancing brings our necessarily communal nature to the fore: For the protection of all we isolate ourselves. Motivated by compassion, we develop each and every solution in the name of the whole. This is, of course, exactly the opposite of the individualist, meritocratic ideology so often defended in capitalist societies.

So we now find ourselves at an inflection point: What kind of society do we want to be? To become? With which end will we choose to align ourselves?

At this moment evangelical institutions and leaders both in Brazil and the United States must rethink their allegiances and dedicate themselves to the global fight against COVID-19. On the occasion of surpassing 100,000 deaths, back in the very distant May of 2020, some evangelical groups in the United States sponsored a National Day of Mourning and Lament. In July, an alliance of Brazilian evangelicals organized a similar event, Lamento 100 mil (“I lament 100,000”). In this time of pain, lament, and grief we must act, whether through instigating acts of solidarity and hospitality or exerting pressure on public officials or defending and reinforcing measures such as social distancing and masking. While doing so, we might also remember the prayer of Habakkuk and in contrition lift anew his question to the heavens: “How long, Lord, must I call for help, but you do not listen?”

Alexandre Brasil Fonseca is a sociologist and Associate Professor at the NUTES Institute for Science and Health Education at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and the author of Evangélicos e Mídia no Brasil (Evangelicals and the Media in Brazil, 2003). From 2012-2016 he was special adviser to the President of Brazil on religious affairs. He is the president of Peace and Hope Brazil. Contact: abrasil@ufrj.br

Alexandre Brasil Fonseca is a sociologist and Associate Professor at the NUTES Institute for Science and Health Education at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and the author of Evangélicos e Mídia no Brasil (Evangelicals and the Media in Brazil, 2003). From 2012-2016 he was special adviser to the President of Brazil on religious affairs. He is the president of Peace and Hope Brazil. Contact: abrasil@ufrj.br