I recently finished a lecture in my Colonial America class at Messiah University on the historiography of the Salem witch trials. We discussed all the major interpretations: Boyer and Nissenbaum, John Demos, Carol Karlson, Elizabeth Reis, Richard Godbeer, Mary Beth Norton, and a few others. I was once again struck by how much anxiety over demographic and political change, fear of the “other,” patriarchy, and theological dogma led to the deaths of nineteen men and women.

If I am remembering correctly, I have only published a few paragraphs on the Salem witch trials. Here is what I wrote in Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump:

Puritan fears about the moral and spiritual decline of their society reached a zenith in 1692. In that year 160 men and women in the colony were accused of witchcraft. Nineteen people were executed by public hanging, and one was pressed to death. The Puritan belief in Satan, demons, and witches only partly explains what happened in Salem and the surrounding towns. New England had seen its share of witch trials over the decades, but the region had not experienced such a scare in more than thirty years. This fact has prompted historians to ask questions about the timing of the witchcraft accusations and why they spread so quickly. Historians of both colonial America and early modern Europe have argued convincingly that witch trials were means by which religious and political leaders dealt with men and women who posed a threat to traditional Christian societies. Many of the Massachusetts residents who were accused by their neighbors of witchcraft–and the clergy and prominent lay leaders who supported those accusations–believed that the outbreak of malfeasance was a clear sign that Satan was trying to deal a deathblow to their godly commonwealth. During the trials, Salem minister Samuel Parris preached from Revelation 17:14, reminding his congregation that “the Devil and his instruments will be warring against Christ and his followers.” He continued: “There are but two parties in the world…the Lamb and his followers, and the dragon and his followers…. Everyone is on one side or another.” This would not be the last time we would witness this kind of dualistic thinking or sense of theological certainty. In fact, as we shall see, it would become a hallmark of evangelical thinking.

The Salem witch trials were a disaster for Massachusetts Bay. Despite warnings from some of the colony’s most prominent ministers, the magistrates used spectral evidence (dreams or visions visiting people in the night and causing or threatening harm) to convict the accused witches and sentence them to death. The speed with which the witchcraft allegations spread throughout northeast New England is evidence of how Christians allowed fear, based on sketchy evidence, to consume them.

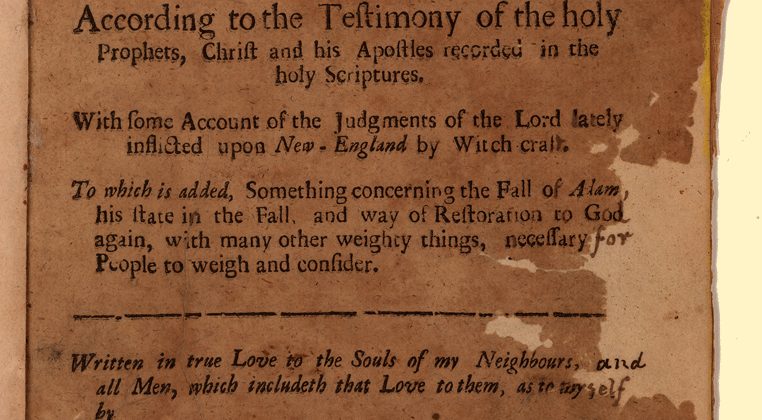

After the hysteria came to an end, many of the participants in the witch trials looked back with embarrassment. Some asked for forgiveness or made public testimonies of repentance. In 1695, Thomas Maule, a member of the Society of Friends in Salem, wrote a tract denouncing his Puritan neighbors for their un-Christians behavior during the witchcraft frenzy. In Truth Held Forth and Maintained, Maule declares: “For it were best that one hundred witches should live, than that one person be put to death for a Witch, which is not a witch.” Maule’s words were a stinging and prophetic critique of the Salem witch trials; they also landed him in jail for twelve months.